Powerful Telescope at Observatory Named for Vera Rubin ’48 Captures Stunning Images of the Cosmos

When noted astronomer Vera Rubin ’48 accepted the Distinguished Achievement Award from the Alumnae/i Association of Vassar College (AAVC) in 2007, she said the College had enabled her to acquire “the confidence that I could learn anything I wanted to know.”

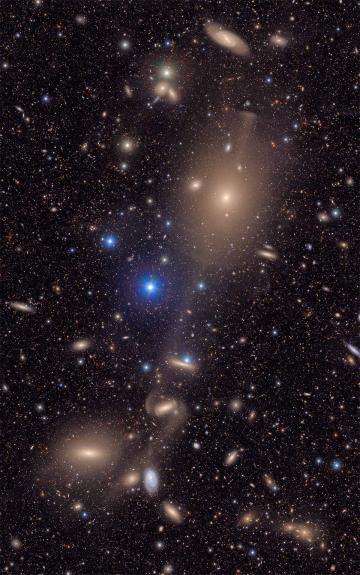

Credit: NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

Eighteen years later, the most powerful telescope on Earth, named in Rubin’s honor, is enabling scientists across the globe to learn a lot more about the nature of the universe. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, located high in the Andes mountains, has begun to send stunning images of the cosmos—from asteroids in our solar system and other near-earth space debris to millions of galaxies thousands of light years away. “The Rubin Observatory is an investment in our future, which will lay down a cornerstone of knowledge today on which our children will proudly build tomorrow,” said Michael Kratsios, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Rubin is most widely known for her groundbreaking research into the nature of dark matter, a mysterious material that has gravity but emits no light, and comprises 85% of all known matter in the universe. The Rubin Observatory will investigate both dark matter and the equally mysterious dark energy, which is causing an ever-accelerating expansion of the universe. Dark matter and dark energy collectively comprise about 95 percent of the universe, but their properties remain largely unknown. Among the first tasks astronomers will tackle with data gathered from the Rubin Observatory will be a decade-long project to glean more information about the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

The Rubin Observatory will be taking more than a thousand images of the Southern Hemisphere sky every night from its perch at the summit of Cerro Pachón in Chile. The facility is jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. It is the first U.S. National observatory to be named for a woman. The observatory’s mirror design, large and sensitive camera, and telescope speed are all the first of its kind, enabling Rubin to spot tiny, faint objects such as asteroids, some of which could be on a collision course with Earth.

Vassar Professor and Chair of Physics and Astronomy Colette Salyk said she knew about Rubin’s ties to Vassar when she joined the faculty in 2015. “I was aware of Vera’s history at Vassar when I came here,” she said, noting the legacy of renowned women astronomers at Vassar had stretched from Maria Mitchell, one of the first faculty members hired at the College in 1865, to Rubin, to Professor of Physics and Astronomy Emerita Debra Elmegreen, who conducted much groundbreaking research using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and several earth-based observatories during her tenure. Elmegreen, who retired in 2022, was acquainted with Rubin and was an admirer of her work, Salyk said.

Credit: Rubin Observatory/NSF/AURA

Salyk said that while her own research doesn’t involve most of the data currently being provided by the Rubin Observatory, she plans to incorporate discoveries Rubin astronomers will be making into her courses. “What’s unique about the Rubin Observatory is its ability to show us so much of the sky repeatedly, over a long period of time,” she said. “This will enable us to spot changes in the cosmos, such as exploding stars, which tell us a lot about the birth of the universe, and to spot exoplanets as they cross in front of stars. It’s almost like a movie instead of the still images we’re used to working with.”

Rubin died in 2016 at the age of 88, but in an interview in the June 2025 edition of Smithsonian Magazine, her granddaughter, Ramona Rubin, said she was certain her grandmother would be pleased about the launching of the observatory. “I think she’d be both deeply moved and also a little overwhelmed by all this recognition,” Ramona Rubin said. “When she was just fighting for observation time at the telescopes, I don’t think she could have ever imagined her name on an observatory in Chile.”