Student Researchers and Their Professors Seek to Understand Prejudice and Empathy

How do children’s explanations for inequality shape prejudice development? And how can adults prevent compassion burnout when every news cycle serves up more suffering? These are some of the questions psychological science students dove into during Vassar’s 2025 Undergraduate Summer Research Institute (URSI)—a unique program that affords closely mentored scientific exploration not typically available at the undergraduate level.

“What we do at Vassar that very few places do is to provide hands-on opportunities for actually touching the data as an undergraduate,” said Abigail Baird ’91, Professor of Psychological Science on the Arnhold Family Chair, herself a former URSI student researcher who went on to earn a PhD at Harvard. Baird said she was grateful that the College was able to continue URSI at a time when many federal grants are being frozen or eliminated—forcing her colleagues at larger institutions to halt their research. “I’m not just blowing rainbows at Vassar but at a time when so many students have lost opportunity in the sciences, the irony is that a small liberal arts college continues to provide top-tier training and is preparing students to be in the laboratory at a time when so many larger research institutions have been forced to reduce or eliminate student positions.”

URSI students will present their research at a fall symposium at the College, but here is a preview of what some of them have been doing this summer.

Photo: Courtesy of Rebecca Peretz-Lange

Mitigating Prejudice Development

Four students worked with Assistant Professor of Psychological Science Rebecca Peretz-Lange to see how parents and other caregivers might be able to leverage young children’s natural aversion to anything “unfair” to help them recognize structural inequalities in society. They also sought to understand kids’ reasoning about why various groups are in different social positions, since kids often wrongly assume that marginalized groups must be internally inferior (rather than externally disadvantaged), an assumption which can foster prejudice.

“Oftentimes they come up with explanations on their own, and we don’t realize it,” explained Sam Vandyck ’27, a member of the project team. “We know from past research that kids view inequalities as deserved and something that the person was born with, or it’s their fault. They don’t see the structural reasons for inequalities.”

As an example, team member Asiyah Abbas ’27 said, “All U.S presidents have been men and none have been women. So why is that? Most of it’s because of voter bias and a lot of barriers for women to get into fields like politics. But a child would immediately jump to inborn qualities [of women] and think that this discrepancy is fair, which it obviously is not,” Abbas said.

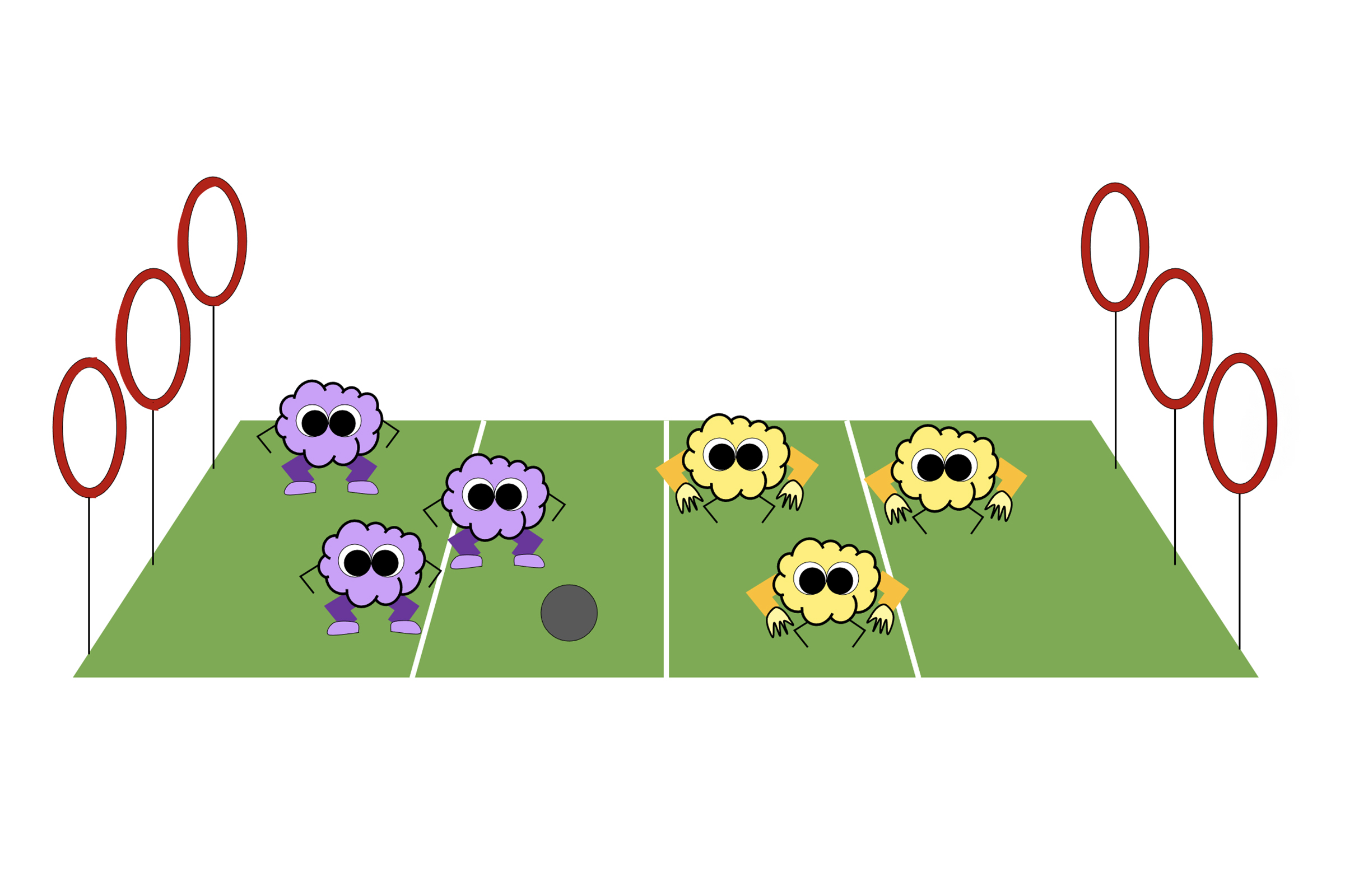

With the help of a cartoon game-based experiment designed by Peretz-Lange, the students are meeting with hundreds of 5- to 10-year-olds in person and over Zoom to understand their reasoning about fairness. In the game, one set of characters has strong arms and the other has strong legs. Points can be scored by either throwing a ball into a high hoop or kicking a ball into a low hoop. But what if the game is structured so that only high hoops are present, and then the characters with strong arms win?

In the first experiment, children watched the game several times with the researchers commenting either “that’s really unfair” or “that’s really too bad” each time. At the end, they asked the children to rate the fairness of the game and also to explain why the losing group lost. Would highlighting the unfairness of the game help them see the structural inequality here? Apparently not.

“It’s actually very interesting because we found that just saying that a situation was unfair did not really make a kid think that the situation itself was unfair,” Abbas noted. “We keep telling the kids, ‘Oh, it’s unfair, it’s unfair, it’s unfair,’ and then at the end of it all, they’re like, ‘oh, yeah, it’s fair,’ which is so baffling to me.”

It would seem, then, that the children need more support in understanding why the game is unfair—a theory that the group is testing in another experiment that draws children’s attention to the hoops to see if this can help children to recognize that the game is rigged. “Our goal is to try to poke holes in children’s views of the world around them so we can kind of target their explanations of the world earlier and create a more equal and fair-minded next generation,” said Vandyck.

No matter how the research turns out, Peretz-Lange said, these students are already furthering that goal by literally changing the face of science for the hundreds of children they’ve spoken with one-on-one. Kids often have the misconception that a scientist must be “a wild-haired White man with a test tube and a lab coat,” said Peretz-Lange, “and we know that that image can really discourage girls and children of color from wanting to pursue science or from even seeing science as something that is accessible or relevant to them. So I think having this diverse group of college students as scientists saying to kids, ‘We’re doing an experiment, I’m doing an experiment, participate with me’ is a really impactful thing that we do as a lab.”

The Costs and Benefits of Empathy

Abigail Baird ’91, Professor of Psychological Science on the Arnhold Family Chair, and Jannay Morrow, Associate Professor of Psychological Science, decided to have their five URSI researchers delve into empathy after a difficult academic year in which they saw many students struggling to stay focused on schoolwork while helping friends with wrenching issues, including deportations.

Photo by Karl Rabe

“Understanding and caring about other people’s experiences, the basis of empathy, is critical to living in a community,” said Baird. At the same time, she said, we are seeing “a world full of so many stressors, from so many sources, that people are experiencing empathic burnout, or what psychologists call ‘compassion fatigue,’ which can make it harder for people to show empathy to others at a time when we need it more than ever.” Morrow added, “We were all interested in knowing more about what might make people better able to engage with others compassionately. Basically, we asked ourselves: What psychological resources or strategies can people turn to that would allow them to be more compassionate, especially when they were dealing with many stressors or challenges in their lives?” They asked their URSI students to take that concept and run with it—both individually and as a group.

Madeline Busam ’26 became intrigued by “self-concept clarity”—the extent to which an individual’s beliefs about themself are clearly and confidently defined. “I initially came about it in my own research, immersing myself in the literature,” she said. “I personally am very interested in the social aspect of personality and so this kind of struck me, and I brought it up in our discussions over the week.”

With her professors’ help, Busam designed a survey to measure self-concept clarity and how it might correlate with compassion burnout and recruited about 300 adults through the data site prolific.com to take it. She is still in the process of analyzing the data, but so far the results are promising.

“We’ve definitely found some stuff that correlates with what I have predicted: That having a higher level of self-concept clarity is going to lead to greater well-being and less compassion fatigue,” said Busam.

Photo courtesy of the subject.

Baird said she and Morrow will continue to work with Busam, who is one of at least two students in this group who will likely be able to publish their studies by the end of Fall Semester. “She’s going to see it all the way through with not one but two professors supporting her as an undergraduate, and that’s a wonderfully unusual setup,” Baird said.

“It’s been very helpful and eye-opening for what I want to do after Vassar,” said Busam, who is considering pursuing psychological science in grad school. “I think I’ve been able to get a lot of skills out of it that I wouldn’t have gotten at a big school where your professor might not even know your name. Being able to work on this small of a scale, one-on-one, has been really amazing.”