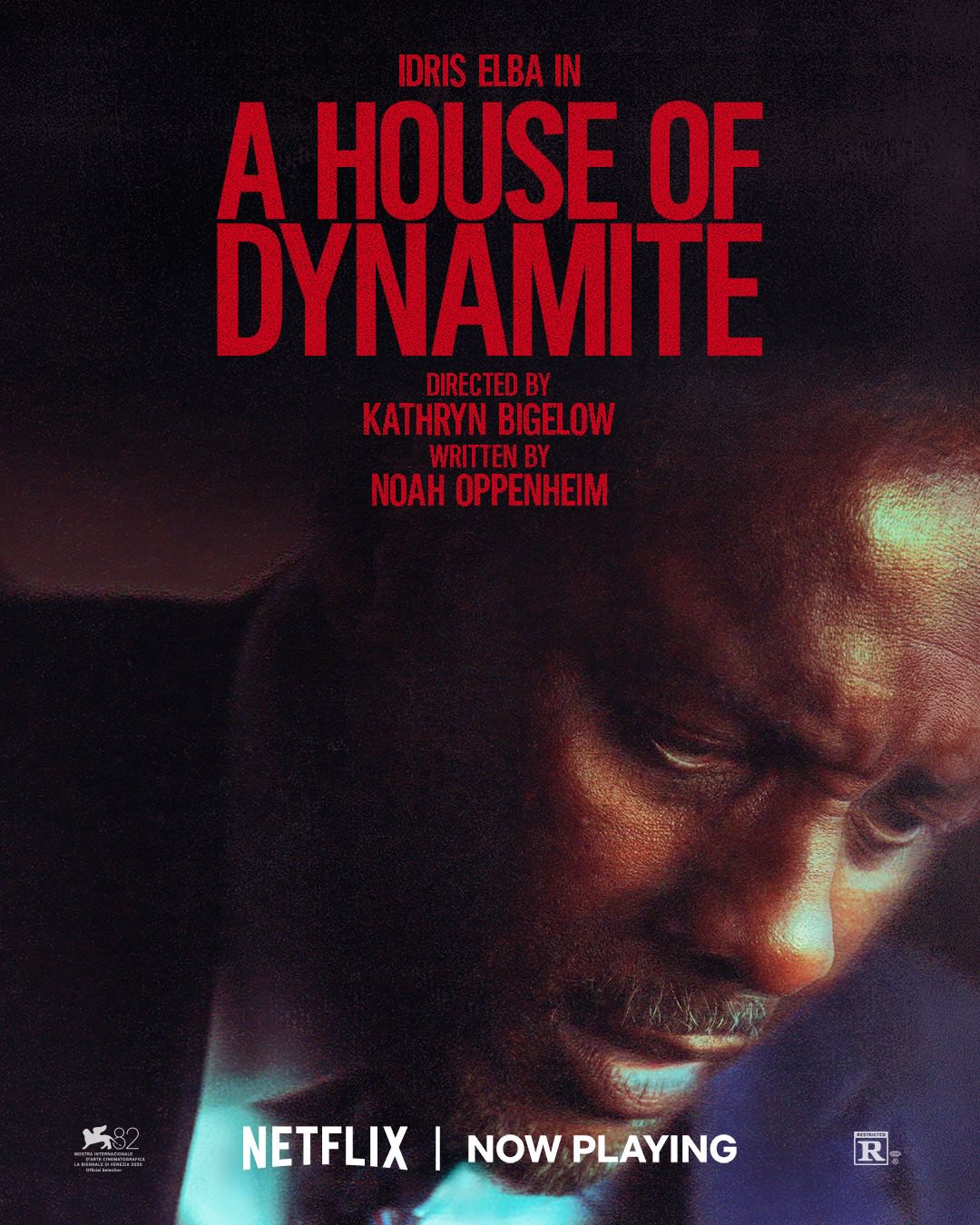

New Thriller, A House of Dynamite, Depicts a Nuclear Crisis Involving the U.S.

The release of the critically acclaimed Netflix film A House of Dynamite, a thriller about the threat of nuclear war, has raised some disturbing questions, including: Could such a “nuclear scare” actually happen? Applying the Vassar dictum “go to the source,” we reached out to Vassar alum James Graham Wilson ’03, Supervisory Historian in the Office of the Historian at the U.S. State Department, for answers.

Wilson and his colleagues sift through government records 25 years old and older and then send them through an interagency declassification process. These declassified documents appear in the publication Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS). His work has included analyses of classified documents pertaining to nuclear scares and nuclear arms negotiations during the Carter, Reagan, and George H. W. Bush administrations. The following are excerpts of our email exchange with Wilson.

Have previous “nuclear scares” taught us anything about how to cope with the next one?

The most serious nuclear scare remains the period 1961 through 1962, during which the Berlin Crisis and Cuban Missile Crisis took place. You can read through the declassified transcripts of National Security Council (NSC) meetings in the FRUS volumes. That must have been a frightening time to live through. A positive outcome from the Cuban Missile Crisis was that the U.S. and Soviet Union set up a direct link—“the Hotline”—between Washington and Moscow.

Throughout the remainder of the Cold War, U.S. and Soviet leaders used the Hotline to convey seriousness of intent—you can see some of these exchanges. Fortunately, we never experienced a repeat of the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and President Richard Nixon communicated with each other—sometimes using the Hotline—to signal each side’s resolve. Fearing a complete collapse of its then-ally Egypt, Moscow broached the prospect of deploying Soviet troops. The United States responded with a heightened nuclear alert that it knew Soviet intelligence would detect. Brezhnev backed down.

Have you had a chance to watch A House of Dynamite? If so, how realistic is the plot?

I plan to watch it when it comes to Netflix, but I have read enough reviews with spoilers to get a gist of the scenario, what happens throughout, and how it ends. I have read former Situation Room directors describe their role in prepping some of the actors and production staff for the movie—and they praise the outcome. So, the depiction of crisis management sure sounds realistic. As a proud alum of the Vassar History Department, I know that I ought not render full judgment without examining the evidence. But is the basic premise realistic? I’m not so sure. Apparently, the movie begins with a single incoming missile popping up on the radar completely out of nowhere. That seems implausible. Especially in 2025, I think the United States would know these things well beforehand.

Courtesy of the subject.

What was the most serious incident involving the apparent launch of nuclear missiles by one side or the other?

Two incidents in 1983 speak to your question. That September, a Soviet military officer named Stanislav Petrov held off reporting a handful of incoming U.S. missiles because he figured it was a false alarm—which it was. A few weeks later came the annual North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) exercise—code name Able-Archer 1983—which Soviet intelligence figured was a prelude to a surprise attack. I think that the risks surrounding Able-Archer 1983 have been overstated. Even if I am wrong in my assessment, you did not have the top leaders of both countries staying up late with their top advisors plotting through steps that hopefully averted a nuclear war, as had been the case during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

What classified documents have you read related to other false nuclear alerts?

The release of A House of Dynamite has led me to revisit the nuclear false alerts of November 1979 and June 1980 that are now declassified and available in national security policy documents from 1977 to 1980. On multiple occasions, U.S. early-warning systems picked up signals of an impending Soviet attack that turned out to be wrong. There were subsequent investigations by the Senate Armed Services Committee and General Accounting Office. These reports were comforting. The gist is that people in the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) did their jobs. They recognized that the computers provided faulty information. That is comforting to know in hindsight. [But] read through these documents from 1979 and 1980, and you do not sense an abundance of optimism at the time. There’s a detail in them about a 47-cent computer chip malfunctioning, and you think: Well, we should have spent more money on such an important chip!

How well prepared is the United States now to recognize false data regarding an impending nuclear attack?

My optimistic take on this is that what happened in 1979–1980 did not happen again during the remainder of the Cold War. I think this is partly because people worked very hard to upgrade the capabilities and ensure that we improved upon these computer systems that fed faulty information. It is also because members of the Reagan administration worked with Soviet counterparts to set up the Nuclear Risk Reduction Center. In the four decades since then, we have seen advanced technologies in space-sensing and a broader array of intelligence platforms that would allow the United States to detect what is happening well before a missile gets to the launchpad.

Does the rise of artificial intelligence technology make it more or less likely that we will face “nuclear scares” in the future?

When it comes to AI and nuclear weapons, negative fantasies about it lie at the heart of WarGames, which came out in 1983, and The Terminator the year after. These movies raised the prospect that AI might someday wage nuclear war either by accident, through cold logic, or simply [for] wanting to get the humans out of the way.

Ronald Reagan watched WarGames, and we know from his diaries that its premise disturbed him. In that movie, the Matthew Broderick character hacks into NORAD to impress the Ally Sheedy character, only to find that he has led an AI supercomputer on the path toward starting World War III. Reagan asked his military advisors whether such a thing could happen. Thinking about that prospect reinforced a position, he jointly proclaimed with Gorbachev in 1985, that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” That is basically what the AI learns toward the end of WarGames, diffusing the crisis—“The only way to win is not to play.”

Does the current geopolitical situation make such crises more likely?

The current geopolitical situation—as I see it—is that the People’s Republic of China, Russia, and the United States are engaged in a new cold war. Does that increase the likelihood of the type of crisis that A House of Dynamite depicts? Again, I think not. None of these “strategic competitors” stands to gain from such a scenario. It is antithetical to their interest to see it happen to anyone else.

But by the 2030s we may find ourselves in a world of three nuclear peer competitors. When it comes to nuclear risk reduction or potential arms control agreements, that would be far more complicated than [between] two parties—the United States and Soviet Union—during the Cold War. This is not precisely what A House of Dynamite is about, yet the timing of the movie may turn out to be a wake-up call to think hard about hard problems that will bedevil us for decades. Simply eliminating nuclear weapons is not a viable option for reducing the risk of nuclear war. I wish that it were.

James Graham Wilson’s views are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of State or the U.S. government.