Celebrating the History of African American Cuisine

Food can say a lot—not just about our tastes, but about our families, our ancestors, our histories. Vassar students will learn more about the importance of the link between food and history during a Black History Month two-day program at Gordon Commons that centers around the Netflix series High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America.

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

On the first day, there will be a screening of Episode One, during which attendees will enjoy foods featured in the documentary series—cooked by our own Bon Appetit food service staff—and participate in a Q&A with Jeh Vincent Johnson ALANA Cultural Center Director Nicole Beveridge.

“I hope the attendees will realize that the food many of us think of as “All American” was born out of the African slave trade,” Beveridge said. “My hope is that we will see food differently after this two-part event.”

Screenings will take place from Noon to 1:30 p.m. on February 15 and 16 on the second floor of Gordon Commons. Sponsored by the President’s Office, Jeh Vincent Johnson ALANA Cultural Center, Campus Activities, and Dining.

The following day, there will be two treats: a virtual moderated discussion with Dr. Jessica B. Harris—the historian and cookbook author whose book, High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America, was the basis for the Netflix documentary (she’s featured in the series, too)—and a tasting menu she recommended.

Some of the anticipated dishes include: Shrimp gumbo, Jollof rice, African black eye pea stew, chicken Yassa, and stewed okra.

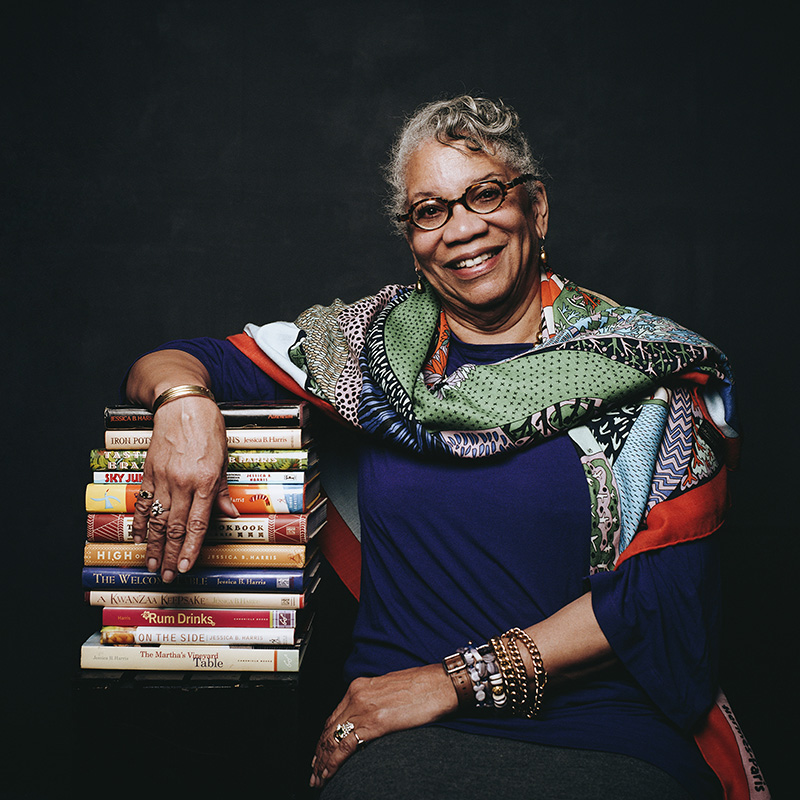

Harris, whose books were inducted into the James Beard Cookbook Hall of Fame in 2019, was a winner of the James Beard Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020, and is a 2021 Time Most Influential People inductee, has chronicled the history of food from the coast of Benin to the tables of America’s restaurants and homes.

In the first of four episodes of the series (which has been renewed for a second season), Harris walks with documentary host Stephen Satterfield, a chef and writer, through the open-air market in Dantokpa, Benin. One topic of discussion is the strong connection between the food of this West African country and African American cuisine that was a result of the transatlantic slave trade.

Photo: Rog Walker

“[A] lot of people from here and through here ended up on the other side of the Atlantic,” Harris said. “It’s not a big place, but it has had an extraordinary impact on the New World … and a lot of that impact is on our stomachs.”

Rice, beans, okra, peppers, and more followed Africans to the North American colonies. In fact, rice was the first big crop in South Carolina—at one point exporting more than 100 million pounds a year—but was a bust until the expertise and labor of incoming enslaved Africans salvaged it, the documentary noted.

This type of connection between history and food makes the Netflix series compelling, and is a common theme among the positive reviews it received.

James Hemings, who trained in Paris while he was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson, brought macaroni and cheese to Jefferson’s Monticello plantation—and the rest of America. Thomas Downing, a Black American, was the oyster king of New York City. The influence of Gullah food from the island off the coast of South Carolina can be seen throughout the state to this day. Texas cowboys, BBQ, Philadelphia’s catering history, pepper pots, and much more are packed into four episodes.

“This docuseries centers Black food culture and the various forms of violence that threaten the future of this cuisine. It made me think of access, privilege, equity, and justice,” Beveridge said. “It also presents a holistic experience of Black food pathways—it satisfies both cultural and culinary history. Some culinary traditions are preserved, while others are inevitably lost.”