Vassar’s Groundbreaking Athletics Program Started with Matthew’s Vision

Vassar’s Groundbreaking Athletics Program Started with Matthew’s Vision

As Matthew Vassar was preparing to meet the students of the college’s first class, one of his top priorities was championing physical activity as an integral part of the new institution’s mission. In the college’s first prospectus, published in May of 1865, physical education was the first discipline to be mentioned.

“This is placed first, not as first in intrinsic importance but as fundamental to all the rest and in order to indicate the purpose of the managers of this institution to give it not nominally but really its true place in their plans,” Vassar wrote. “In carrying out…the thorough physical training of our students, extensive arrangements are to be made on the grounds for various gymnastics and athletic exercises, healthful recreation and physical accomplishments suitable for young ladies.”

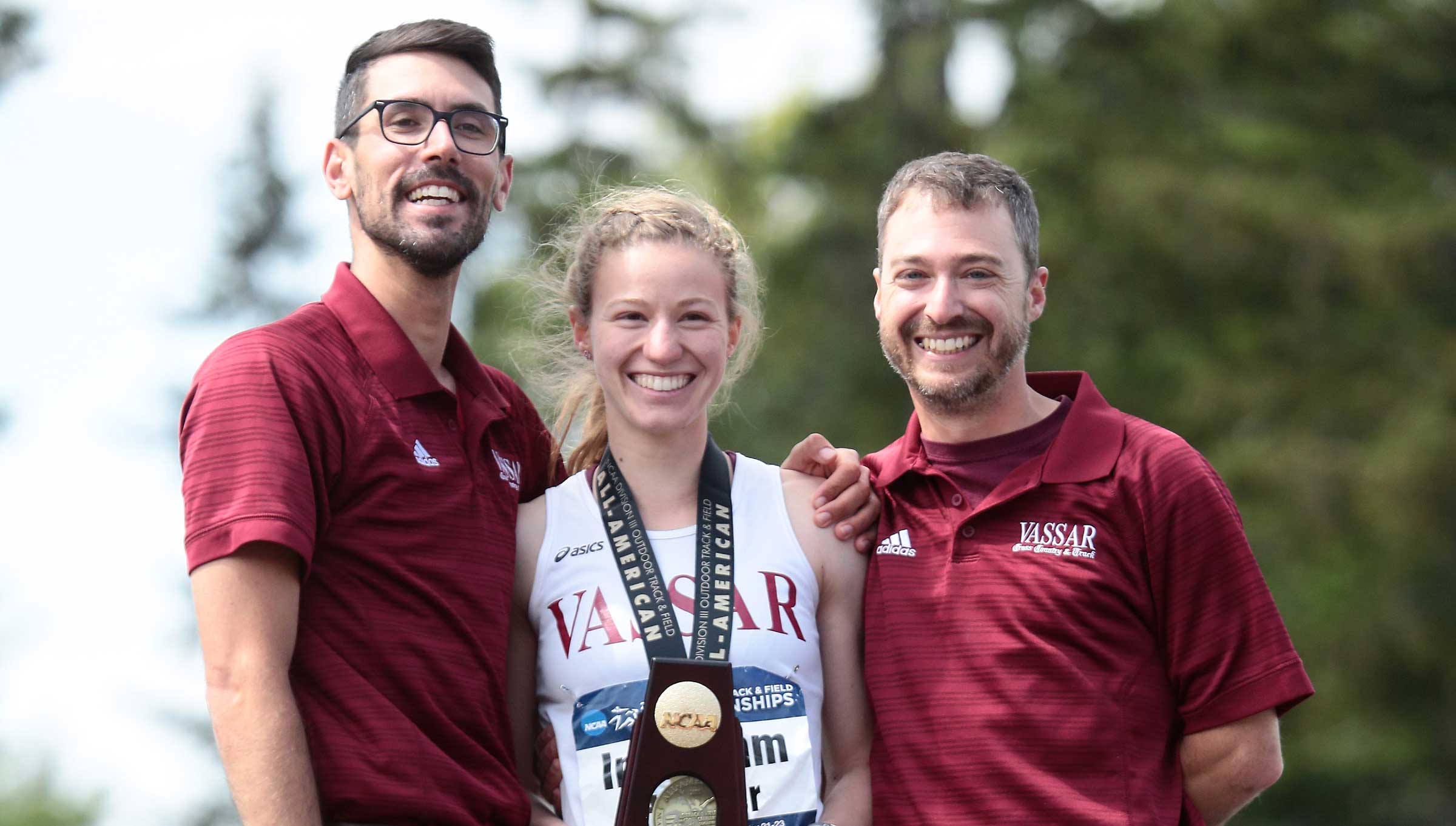

Exactly 150 years later, on May 23, 2015, Heather Ingraham ’15 became Vassar’s first national intercollegiate champion, winning the 400-meter race at the NCAA Division III Track and Field Championships in Canton, NY. But throughout the college’s history, its students, faculty and administrators have embraced its founder’s belief in the importance of athletics and other physical activities.

In 1898, Vassar alumna Margaret Pollock Sherwood, class of 1886, a professor at Wellesley College, published an article in Scribner’s Magazine titled, “Undergraduate Life at Vassar College.” In it, Sherwood wrote, “The college girl is not put to sleep by it, but is roused to physical activity. There is rowing on the lake. Golf has faithful adherents, judging by the number of flags shining against the grass. Basketball now occupies the charmed circle bordered by the cedar hedge, and new tennis courts have been made near the pine walk that borders the grounds. The 1897 Vassarion gives an almost startling result of the athletic training: “Field Day, in the spring, is given up to contests.”

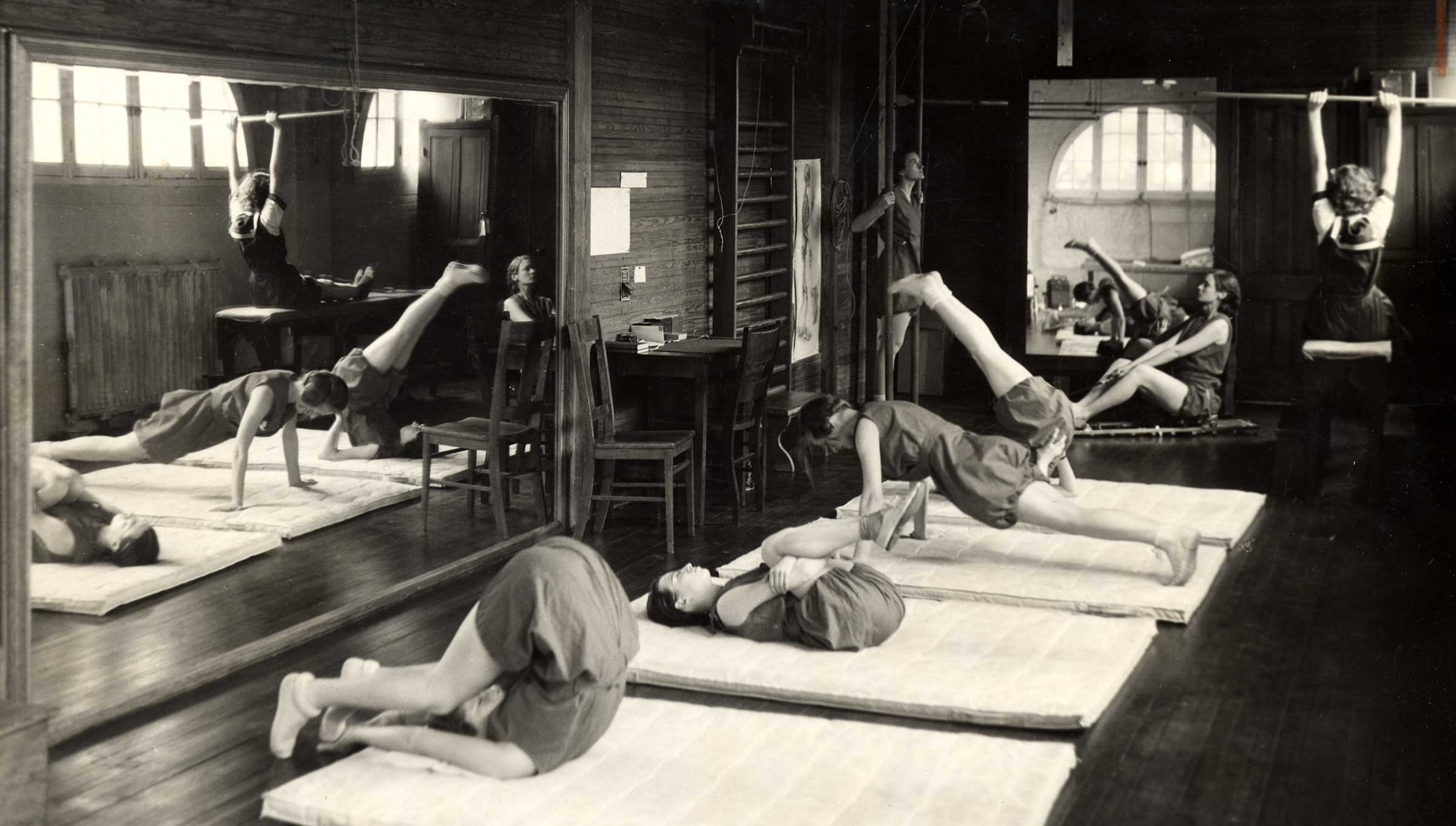

The importance of athletics and physical training in Vassar’s early years was exemplified by the construction of the “Calisthenium and Riding Academy (later renamed Avery Hall) in 1866, which housed a riding school with stalls for 25 horses, and Alumnae Gymnasium (later renamed Ely Hall) which housed a swimming pool, that was completed in 1869.

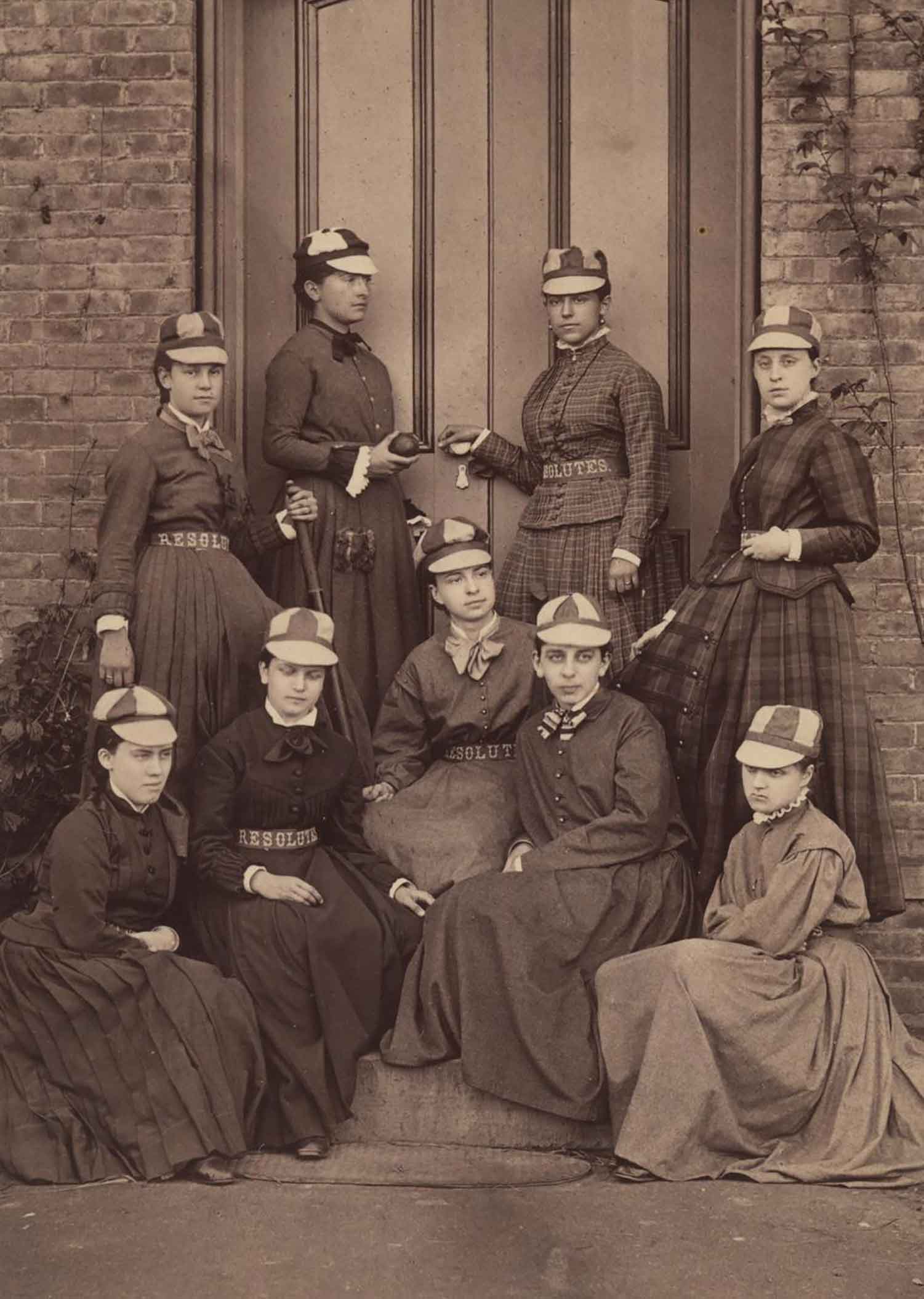

A former Prussian cavalry officer, Leopold von Seldeneck, was hired to give riding lessons, but the academy was abandoned six years later because it was deemed to be too expensive. Meanwhile, other athletic activities were thriving. In her book, The History of Physical Training at Vassar College, 1865-1915, Harriet Isabel Ballintine, Vassar’s Director of Physical Education in the early 1900s, notes that calisthenics were a regular part of the curriculum when the college first opened, and numerous other activities blossomed soon afterwards. “By 1866, a light croquet club was formed, and the Laurel Baseball Club played games on Saturday afternoons,” Ballintine wrote. Rowing was also popular, featuring boats with such whimsical names as “Feather,” “Maid of the Mist,” and “Water Witch.”

As varied as Vassar students’ interest in athletics may have been in those early years, it was its baseball teams that have captured the most media attention. Following are excerpts of accounts of women’s participation in the sport in the sports blogging network SB Nation:

“The first baseball teams, Laurel and Abenakis, were created in 1866, each featuring nine women. One of the creators, valedictorian Annie Glidden [class of 1869], wrote to her brother John about the creation of these teams, joking that ‘we think after we have practiced a little, we will let the Atlantic Club play a match with us.’

“While the women were allowed to form baseball teams, the sport was considered to be far too manly to be truly beneficial for them. The players had to provide their own equipment, and the field was rough and hidden from the rest of the school. Women were allowed to play baseball, but only barely. The next year, both Laurel and Abenakis had disbanded, and no woman on either team was present on the Precocious club, the teams’ replacement. This kind of turnover continued until the early 1870s, when the school buckled under public pressure and finally parroted the falsity that the sport was far too manly for these women of high society to play.”

Vassar women were quick to take part in other sports as soon as they learned about them. In 1895, four years after James Naismith invented basketball in Springfield, MA, Vassar had formed some teams on the campus. And in 1901, when British athlete Constance Applebee first introduced field hockey to the United States, she was hired to teach the game to Vassar students for a week, and several house teams were formed almost immediately. Fencing was also introduced in the early 1900s, and athletics received a major boost when new tennis courts were installed, and a modern swimming pool opened in Kenyon Hall in 1934.

In 1937, one of Vassar’s sports legends, Betty Richey, began her 41-year tenure as a coach of field hockey, lacrosse, squash, and tennis. One of Vassar’s major annual awards, given to the male and female players who had the most outstanding seasons, is named after her.

In 1972, three years after the college became coed, the men’s and women’s track and field teams were established. Vassar joined the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 1981, and Dick Becker was named the college’s first Director of Athletics. A year later, Walker Field House, a 42,250-square-foot venue for swimming, basketball, volleyball, and fencing, was constructed. Vassar joined the Liberty League in 1999, the Athletics and Fitness Center was built in 2000, and the Prentiss Field Complex was renovated in 2008.

As Vassar’s athletics programs continued to grow, the women’s teams continued to thrive. On December 2, 2018, the perennially strong women’s rugby squad became the first in the college’s history to win a national team championship. The Brewers defeated Winona State University, 50-13 in the finals of the USA Rugby Division II Fall Nationals in Charlotte, NC.

In her remarks to Vassar’s Board of Trustees in 2015 following her appointment as Director of Athletics and Physical Education, Michelle Walsh said she was proud to have the opportunity to be a part of the college’s remarkable athletics legacy. “I am deeply honored to be part of the Vassar athletics family that has a rich and distinguished tradition dating back to the founding of the college,” Walsh told the trustees. “Matthew Vassar’s vision was to offer women access to ‘the most perfect education of body, mind, and spirit.’”

Walsh said she was certain Matthew would be pleased to see the fruits of his vision. “As we continue his legacy, our athletics and physical education programs are getting better and better,” she said. “Last year for the first time, we had three women’s teams—field hockey, soccer and cross country—competing in Liberty League championship playoffs. The history of women’s sports at Vassar informs our current teams.”