Vassar For ActionReckoning with the ConfederacyConnor Towne O’Neill ’11

Vassar For ActionReckoning with the ConfederacyConnor Towne O’Neill ’11

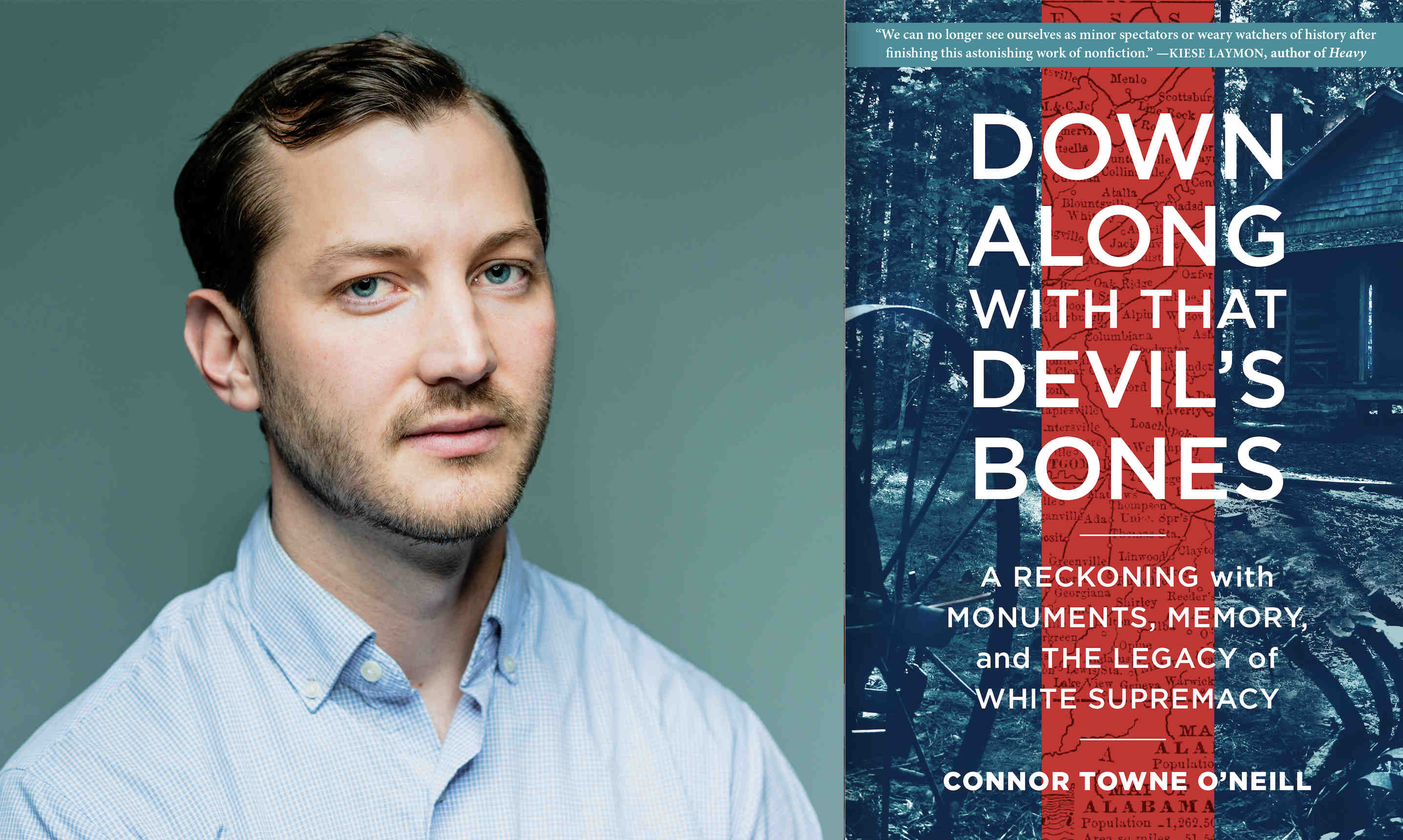

A couple of years after Pennsylvania native Connor Towne O’Neill ’11 moved to Tuscaloosa, AL, for graduate school, a chance encounter with supporters of Confederate monuments led him to undertake a deep dive into the pitched battles over them. The result is Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy, his first book.

Through the lens of conflicts over monuments to notorious Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, O’Neill examines how the repercussions of slavery continue to shape the country. He employs a mixture of history, reporting, and memoir.

“The debate about Forrest’s legacy threw into relief what was at stake in everything from police shootings to national anthem protests, white supremacist rallies to immigration debates,” says O’Neill, who teaches English at Auburn University in Alabama and is a producer for the NPR podcast White Lies. He spoke to VQ about his revelations while studying Southern history as a native of the North.

How did this book come about?

In 2015, I was attending the 50th anniversary commemoration of Bloody Sunday, when civil rights protesters marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma were beaten by police officers. I was looking for parking, and I turned into a cemetery and ended up meeting a group of neo-confederates who were doing upkeep on a plot because they were getting ready to replace a bust of Nathan Forrest. I wondered who Nathan Forrest was, and what it meant to put up a statue of him in 2015. I learned he was a vicious Confederate general who oversaw the massacre of black troops surrendering at the Fort Pillow Massacre in 1864. Later he served as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. His life touched on the worst parts of racial violence in America. In Tennessee, as of the last tally, there were 30 monuments to Forrest—more monuments than the state has honoring all three presidents from Tennessee—Polk, Johnson, and Jackson.

How did studying the legacy of white supremacy change your thinking about yourself and white privilege?

As a white Northerner, I was taught to think of this history as something that happened “down there.” It was a Southern problem, and courageous people like Martin Luther King Jr. stood up and solved it, and we can all dust our hands off and move past it. But the more I started to engage with questions about race and the legacy of slavery, the more I began to understand that ideas about blacks and whites, and the social construction of race, had shaped my life in Pennsylvania as much as anywhere. It’s just closer to the surface in the South.

Forrest was fighting to maintain a system where the board was tilted for white men like me, and the board is still titled in my favor. Even 150 years after the war, the American system protects wealth and opportunity for people who look like me.

How did your experience at Vassar contribute to writing this book?

Many of the seeds that grew into the book were planted at Vassar. Classes in the Latin American studies department helped me challenge naïve ideas about America and America’s sense of itself. And [Associate Professor of English] Eve Dunbar taught a class about blues and African American literature that was incredibly important to me. Eve asked a question that I’ve been wrestling with ever since. I had been writing about the blues, traveling to Mississippi, just beginning to understand the legacy of racial violence and how it has shaped this country, when she asked me, “What does it mean to be alive to American history?” I think in some ways the book is my attempt to answer that question.