URSI and Ford Scholars Learn Research Can Be Frustrating—and Fun

URSI and Ford Scholars Learn Research Can Be Frustrating—and Fun

Professor of Mathematics John McCleary has a coffee cup in his office inscribed with the words, “Try again, Fail again, Fail better.” The wry aphorism, taken from Samuel Beckett’s 1983 novella, Worstword Ho, serves as a reminder to McCleary and his students that failure is a common—and necessary—component of all scholarly research.

Every summer, approximately 60 Vassar students learn to experience failure—and also find plenty of success—in independent research they undertake with Vassar faculty. The students engage in science projects under the auspices of the Undergraduate Research Summer Institute (URSI), and they conduct research in the humanities and social sciences under Vassar’s Ford Scholars program.

This summer, the students took part in 39 research projects with faculty in 19 academic departments. Students in the URSI program will display their work at a symposium on September 25. The Ford Scholars Symposium will be held on September 16.

McCleary says the summer programs offer Vassar students the opportunity to learn what original academic research is all about. “Our students may be able to find research opportunities elsewhere, but the fact that Vassar has something for them right here on the campus every summer is truly a valuable thing,” he says.

Following are brief looks into several URSI and Ford Scholar projects:

“Tensegrity: Theory and Practice,” Nicolas Demaria ’21, Matthew Goldberg ’20 and Professor of Mathematics John McCleary

Before they filled out their applications for their URSI project, neither Nicolas Demaria nor Matthew Goldberg had ever heard of tensegrities. But within a few days, they were building them.

“I had to ‘Google’ the word when I saw it on the application,” says Goldberg, a mathematics major from Cambridge, MA. “This was the perfect project for me. Tensegrities are an intersection of art and math, two of my passions.”

The word—a fusion of “tension” and “integrity”—was coined by architect and systems theorist R. Buckminster Fuller to describe the combination of tension and compression that is required to enable the objects to become rigid and stable.

Demaria, a mathematics major from New Hyde Park, NY, says he and Goldberg used numerous materials to build their objects, and some worked better than others. “We tried PVC piping, Popsicle sticks, rubber bands, and fishing line,” he says. “We quickly learned that fishing line is very hard to work with.”

McCleary says he was impressed, but not surprised, by how quickly his students had figured out how to build tensegrities. “For this URSI project, I was looking for students who were willing to work hard, become frustrated and keep working just as hard, and that’s what Nic and Matt have done,” he says.

The project culminated with a conference on tensegrities on the Vassar campus organized by McCleary through a grant from the National Science Foundation. The conference drew more than 30 mathematicians and other scholars from colleges and universities throughout the United States as well as England and Italy.

McCleary says Goldberg spoke at length during the conference with Cornell University mathematics Professor Robert Connelly, who has used tensegrities to enhance his study of the theory of rigidity. “Matt and Bob were really engaged in lots of discussion about their work,” he says.

Demaria says he thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to tackle a project he knew “absolutely nothing” about when he began. “It was definitely a different type of learning,” he says. “We had no textbook to learn from, and we definitely found that failure is a big part of research.”

Goldberg agreed. “There were times when we’d come up with a new concept and think we were geniuses, and then we’d find out that someone had already written a paper on it,” he says. “But it was gratifying to know that our thinking was on the right path. This was a crash course in learning how to learn.”

“Plant Diversity in Iceland,” Samantha Sze ’21, Anna Elewski ’21 and Professor of Biology Mark Schlessman

Samantha Sze, Anna Elewski, and Professor Schlessman spent five weeks in a remote corner of Iceland, identifying and collecting more than 125 plant species. They donated one sample of each of the plants to the Skálanes Nature and Heritage Center in Iceland and another to the New York Botanical Garden. They brought the rest of the samples back to Vassar.

Schlessman says the project had two goals. “We wanted to provide a set of our samples to the (Skálanes) ecotourism facility in Iceland so researchers who go there later will have a baseline of the plant species in the area, and we wanted to have a set of samples for future classes and research here at Vassar,” he says. They provided the third set of samples to the New York Botanical Garden because officials there had given them a permit that enabled them to bring the plants back to the United States.

Sze, a biology major from Brooklyn, NY, had taken a course last year on the collection and cataloging of plants, but the experience was entirely new for Elewski. Both students said they learned to quickly identify many of the plants after just a few days on the job in Iceland. “After a short while,” Sze says, “both of us could identify many of the plants from a distance. I was surprised by how sharp the learning curve was.”

Once they identified a plant, Sze and Elewski recorded its GPS coordinates and took a digital photograph of the plant and its nearby habitat. A map depicting all of the plant species they identified will appear on a Vassar Biology Department website.

Elewski, a biology major from Olympia, WA, says the project helped her in making career plans after she graduates. “It confirmed for me that this is the kind of field research I want to do,” she says. “The project was definitely a collaboration that worked well; we’re both self-driven.

“It’s a great feeling having these skills now,” Elewski continues. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience doing this work in a beautiful place.”

Schlessman said he was impressed by how quickly Sze and Elewski learned the intricacies of their field work. “Samantha and Anna became adept at identifying species using a field guide to Iceland's flora, photographing the plants in their natural habitat, recording relevant collection data, collecting materials for herbarium specimens, and pressing those specimens in the field,” he says. “Knowing what to collect and how to press it properly is an important skill, because that determines how useful the finished herbarium specimen will be. A good herbarium specimen should last hundreds of years. They worked out a system of sharing these tasks, becoming a highly efficient collecting team.”

“Ecological Mapping and Assessing,” Benji Mathot ’22, Rachel Strout ’20, and Keri VanCamp, Manager of the Vassar Farm and Ecological Preserve

Vassar’s 415-acre Ecological Preserve serves as a living laboratory for students in numerous academic fields. Its forests, fields and wetlands provide myriad opportunities for Vassar students to learn about the natural world. And because of its location—it is surrounded by urban and suburban territory—and the recent arrival of the emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle that VanCamp says will probably kill most if not all of its ash trees, the plants and wildlife on the Preserve face significant challenges.

This summer, under the direction of Field Station and Preserve Manager Keri VanCamp, two Vassar students and two members of the Student Conservation Association took the preserve’s “pulse.” They collected and identified plants, water creatures, and other animals on the property, and they monitored gaps in the tree canopy caused by the dying ash trees.

“What we did this summer is part of a five-year study that will help us plan for the future,” VanCamp says. “Five years from now, we will conduct another census and compare the results to make future decisions for the preserve.”

URSI student Benji Mathot ’22, a prospective biology major from Boise, ID, collected samples of tiny waterborne micro-invertebrates that help scientists measure the health of streams and wetlands. Mathot says his research indicated that the health of some of the streams could be better.

“If I’m finding the kind of animals that can’t tolerate pollution very well, that’s a sign that the stream is healthy,” Mathot explains. “If I’m finding mostly creatures that are more tolerant of pollution, that’s an indication the water quality has some issues, and that’s what I’m finding.”

Rachel Strout ’20, a biology major from Natick, MA, collected samples of plants throughout the preserve, including areas that are losing shade due to the death of the ash trees. “The emerald ash borer is changing the tree canopy, and that will change the kinds of plants we are finding,” Strout says. “I took a course in plant identification last year, but it’s amazing how much faster you learn when you’re out in the forest.”

Strout says her experience in the URSI program helped solidify her post-Vassar plans. “One of the reasons I chose Vassar was because the preserve was here,” she says. “The work I’ve done here has confirmed for me that this is the kind of work I want to do.”

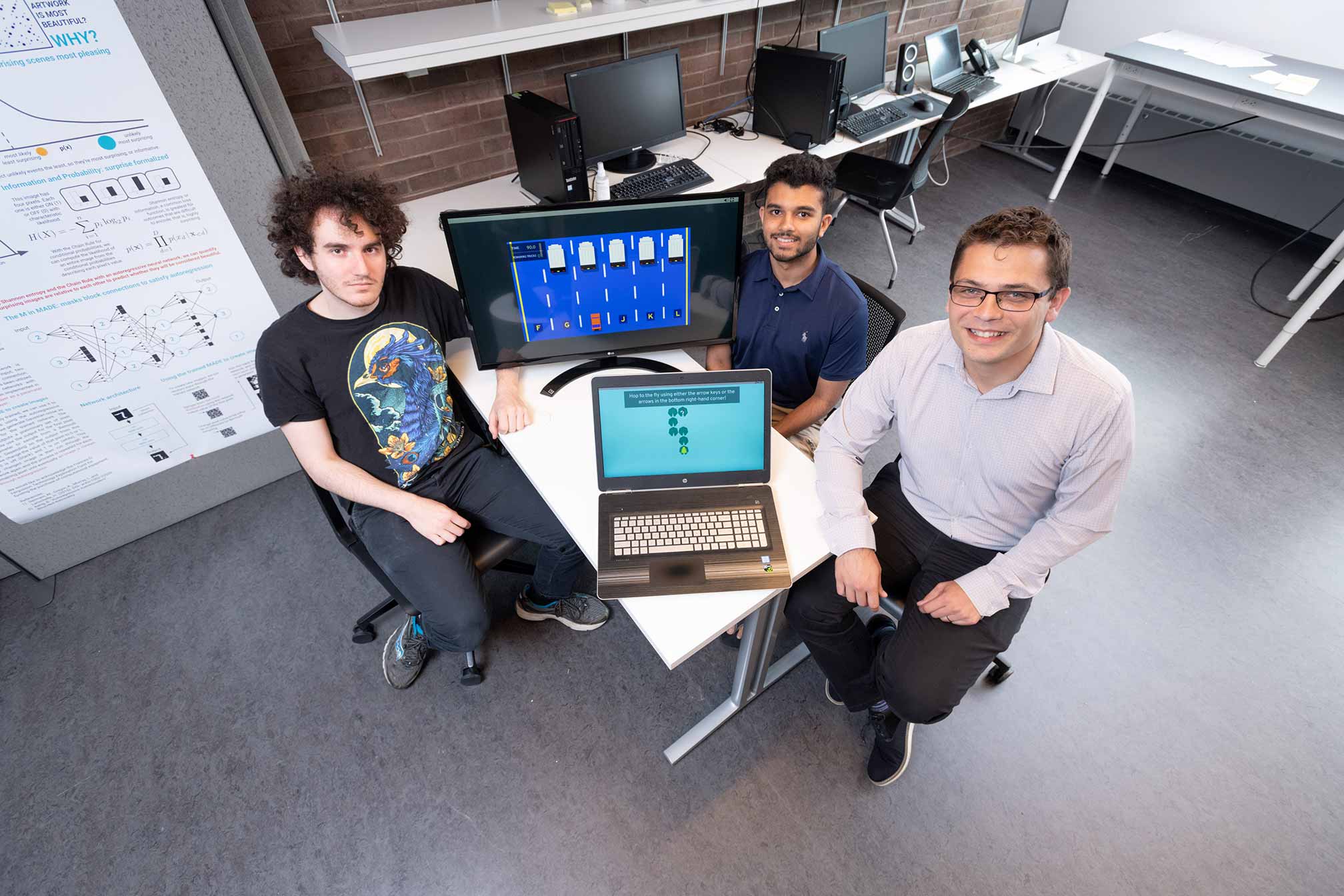

“Human Cognition in Online Games,” Noah Ari ’20, Jonayed Ahmed ’20, and Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science Josh de Leeuw

Video games are fun to play, and for those with the know-how, they’re also fun to build. But they can also serve as a useful tool in helping scientists determine how we learn. This summer, Noah Ari ’20 and Jonayed Ahmed ’20 created and built games that they hope will help other researchers learn more about how fast we learn.

In Ari’s game, “The Forgetful Frog,” players help the frog chase a fly as he hops from one lily pad to another. As the game continues, the patterns of the lily pads change. As players begin to discern these changing patterns, they are able to catch the fly more quickly.

Ahmed’s game challenges players driving a car to pass a line of trucks that are in front of them on the highway. As players learn the pattern of the trucks’ movements, they learn how to maneuver their car through the traffic.

Ari and Ahmed will place their games on an online platform, Prolific, where players are invited to try them out. “Our end goal is to develop our own site to track the data on all players,” says Ahmed, a computer science major from Poughkeepsie, NY.

He says he and Ari faced some challenges figuring out how to design a game that tracks players’ progress. “It’s fun to think back and remember all the hurdles we cleared,” Ahmed notes. “We cleared some in a couple of hours, but it took a couple of weeks to clear others.”

Ari, a computer science major from Jacksonville, FL, says he enjoyed building a game that may help others conduct their own research. “The project caught my eye initially because it was about building games,” he says, “but the added component of using them to gather data on people’s ability to learn has sparked my interest in other aspects of cognitive science.”

Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science Joshua de Leeuw says he enjoyed watching his URSI students experience the challenges of independent research, solving problems on their own rather than finding the answers in a textbook.

“I picked these guys for this project because they were so motivated to learn,” de Leeuw adds. “There were times when I’d be away for a while, and it was fun seeing how many problems they’d solved when I got back.”

The games are close to completion, and will be available shortly at www.thebraingamelab.org.

“Developmental Movement for Infants and Caregivers,” Athena Davis ’20, Alexandra Blaine ’20 and Associate Professor of Psychological Science Carolyn Palmer

“If you know what you’re doing, you can do what you want.” That’s how Israeli engineer and physicist Moshe Feldenkrais once summed up his system of physical exercises aimed at improving human functioning by increasing self-awareness through movement.

This summer, Vassar students Alexandra Blaine ’20 and Athena Davis ’20 applied Feldenkrais’s techniques, putting some of their peers through exercises that enabled them to recall some helpful movements they had learned as babies. “We were teaching people to re-learn things they didn’t know they had learned,” says Davis, a biology and Africana Studies double major from Ramsey, NJ.

Davis and Blaine designed nine separate exercises mimicking babies’ development. Their test subjects began by lying on their backs, then advanced to rolling and crawling, and finally standing and walking. After they finished each of the exercises, the subjects answered a series of questions that helped them understand what their bodies were experiencing. “The key was getting our subjects to develop an awareness of what their bodies were doing,” Blaine says.

Blaine, a psychological science major from Charlottesville, VA, said the research was especially interesting because she and Davis approached it from slightly different perspectives. “I came to the project with a background in how people think, while Athena had more knowledge about body structure and how the muscles behave,” she says.

Davis notes that the research not only benefited the researchers, but also the subjects of the experiments. “It was gratifying to get feedback from actual humans,” she says. “They told us they actually slept better after gaining more awareness about their bodies.”

“The Impact of Declining Mexican Migration on U.S. Labor Markets,” Matthew Park ’20 and Associate Professor of Economics Sarah Pearlman

Matthew Park ’20, an economics and mathematics double major from Philadelphia, used U.S. Census data and other government databases to determine what kind of jobs migrants from Mexico and other countries are finding when they come to the United States. He says he found that recent Mexican immigrants are more likely to have skilled jobs, while the low-income jobs they once held are now being filled by those from Central America and Asia.

Park also studied migration patterns of immigrants once they arrived in the United States and learned many Mexicans are leaving the Southwest and moving to the Northeast.

Noting that he hadn’t studied immigration before he was selected as a Ford Scholar, Park says it took him some time to work with the software required to gather the government data. “The first week was a little unnerving,” he says, “but Sarah was a good mentor, and research about immigration interested me because I am a first-generation American myself. My parents immigrated here from Korea.”

Park says his summer as a Ford Scholar helped him become a better student. “Research is definitely a messy process,” he adds. “I’d often start out seeking the answer to one question and that would lead to many other questions. I can definitely say I learned a lot about solving problems on my own and taking more responsibility for my work.”