Cracking the CodesVassar Alumnae Deciphered WWII Enemy Communications

Cracking the CodesVassar Alumnae Deciphered WWII Enemy Communications

With war raging in Europe and Asia, and the U.S. on the brink of entering World War II, the government knew what it needed—educated women who could take over the duties of men who were needed on the battlefield. The U.S. Army and the Navy, however, had a vital, top-secret task that needed the country’s very best female minds—and so they set out to women’s colleges to recruit them.

In 1941, the presidents of the Seven Sisters met at Mount Holyoke to discuss the need for these women to work in Washington, DC. The army and navy had approached the schools seeking students who excelled in math, science, and foreign languages—and who had the ability to keep a secret.

Candidates at the Seven Sisters were quietly sent invitations to take private courses, with the aim of determining whether they had what it took to be involved in one of the most important and secretive jobs in the war—deciphering coded enemy messages.

The endeavor is chronicled in Liza Mundy’s book Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II. The details unearthed in her research describe the journey in the lives of the women who heeded the call. Women like Elizabeth Sherman “Bibba” Arnold ’37, a Vassar-educated mathematician, Edith Reynolds ’44, and Elizabeth Bigelow ’44, all of whom worked in the cryptanalysis—code breaking—unit for the U.S. Navy.

In total, 197 Seven Sisters alumnae answered the initial invitation to come to Washington, DC, in the spring of 1942. There they were joined by women recruited from other women’s colleges and a variety of professions, most notably teachers. But it wasn’t until their first day at work that the women were made aware of the true nature of their mission and the burden that would be placed on their shoulders.

“For a code breaker, no situation is more stressful than knowing lives depend on your own success or failure. If you crack the code, people will live. If you don’t, they may die,” Mundy wrote.

During WWII, women from colleges like Vassar were recruited to work on a project so secret that most didn’t speak about it until 50 years after the fact.

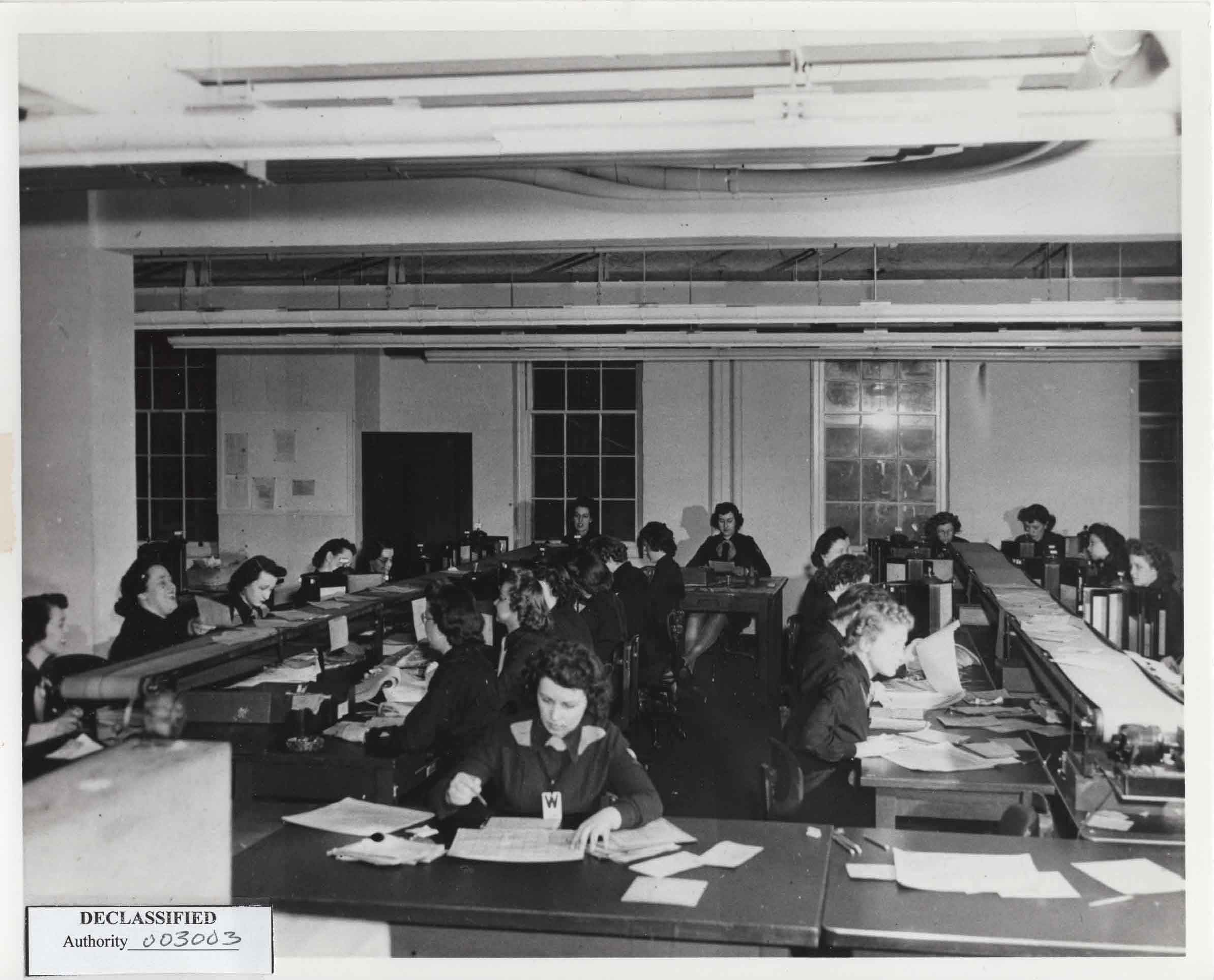

The women went to work immediately. Many were responsible for breaking codes, but others performed vital tasks such as keeping a library of war details—ship names and locations, troop movements, convoy routes, etc.—and sifting through thousands of intercepted messages and identifying those that seemed important.

At the outbreak of the war, the army and the navy operated separate cryptanalysis units. The navy took possession of a private girls’ school and erected barracks to house 4,000 female code breakers. The army converted a former girls’ finishing school into Arlington Hall, which served as its massive code-breaking facility. Those who didn’t find lodging on-site were housed in hastily built barracks and city boarding houses. Some of the women pooled their money together to rent small apartments, taking turns sleeping in the sole bedroom as they worked different shifts.

The women performed high-pressure and often monotonous work in one of three shifts within the navy and army’s 24-hour, around-the-clock schedules. Most would spend the next few years deciphering codes that obscured vital information on strategy, troop movements, shipping itineraries, political alliances, and more.

Those working for the navy had to contend with Japanese messages, which were created using several codebooks, each with hundreds of pages of ciphers. Those working for the army tackled messages from the European theatre, where Germany’s dreaded Enigma machine seemed impossible to crack. The women, working in small groups, would be given intercepted messages. They would search for keys to unlock their meaning, poring over them for hours, days, weeks, and sometimes months. They scanned for common numbers used in identical sequences, or other clues that would help decipher some of the letters. The women worked with male counterparts in Great Britain and Australia, and with U.S. servicemen overseas, pooling their knowledge with the hopes of deciphering the codes.

“It was boring, tedious work, except when it wasn’t,” wrote Mundy. “Elizabeth Bigelow [’44], an aspiring architect recruited from Vassar, also began working on JN-25 (the Japanese fleet code)… She at one point was giving an urgent but badly garbled cipher and asked to decipher it, which she did, in a matter of hours. It told of a convoy sailing later that day. When she was told that her work had helped to sink the convoy, she later said, ‘I felt terribly pleased.’”

While there might be fleeting feelings of elation, the women never forgot the task at hand. Nearly all had family members, friends, or fiancés serving in the war. Bigelow lost a brother who was fighting in the Pacific. More than one code breaker deciphered a message that told the fate of a loved one.

The women were forbidden to talk about their work and were advised of the harsh punishments that awaited those who leaked information. The female code breakers were paid less than their male counterparts, and in many instances, weren’t eligible for advancement (most were civilians contracted to work for the armed services), though some, like Bibba Arnold, were so remarkable that they were put in charge of entire units.

Each year through 1944, new summons were sent to students at the Seven Sisters and other women’s institutions of higher learning. Reynolds was only 16—she had skipped two grades in elementary school—when she received a letter inviting her to a private meeting in Thompson Memorial Library.

Along with other Vassar alumnae, Reynolds and Bigelow eventually became members of the navy’s women’s reserve, Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). More than 10,000 WAVES worked in Washington, DC, during the war. In total, 7,000 women made up 70 percent of the army’s cryptanalysis unit and another 4,000 women comprised 80 percent of the U.S. Navy’s program.

A secret unit of African American women was also recruited to tackle commercial codes, “keeping tabs on which companies were doing business with Hitler or Mitsubishi,” the book notes.

Women code breakers helped with major victories during World War II, including the Battle of Midway and other Pacific theater successes such as the shooting down of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. They were responsible for breaking major code systems, keeping track of German U-boat locations and Allied convoys, and operating the machines that attacked the Enigma ciphers, Mundy notes.

“During the most violent global conflict that humanity has ever known—a war that cost more money, damaged more property, and took more lives than any war before or since—these women formed the backbone of one of the most successful intelligence efforts in history,” Mundy wrote.