Not Your Average CowgirlFrances Rosenthal Kallison ’29

Not Your Average CowgirlFrances Rosenthal Kallison ’29

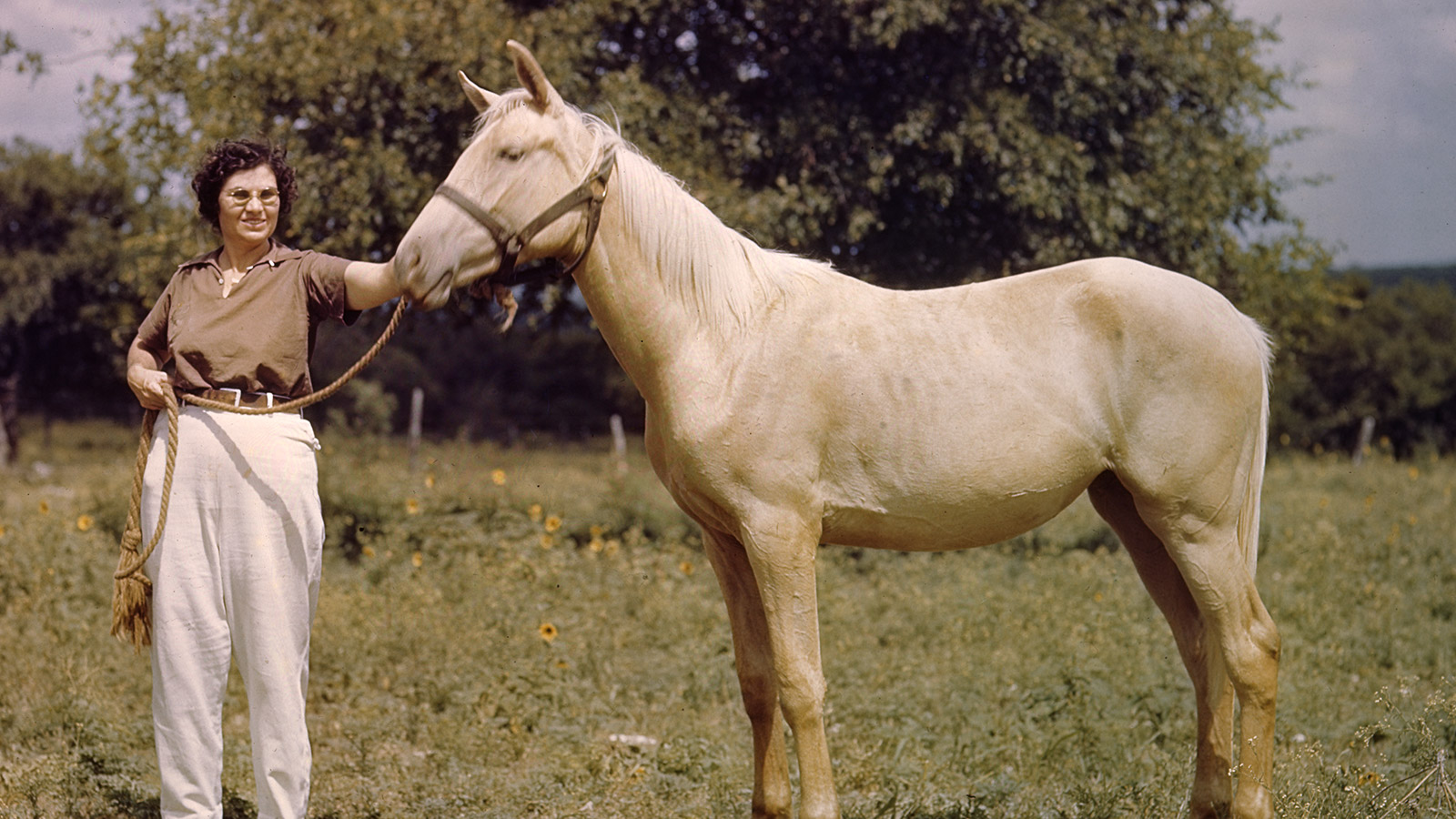

When people think of the word “cowgirl,” they might not picture someone like Frances Rosenthal Kallison ’29. Sure, she was a proud Texan who helped run a cattle ranch and bred and rode palomino horses, but she also served on numerous boards, created charities for those in need—and never left the house without donning her white gloves.

“She was this hybrid—kind of a rawboned person in certain ways, and very high-minded and philanthropic in other ways, and still Victorian in her outlook on things,” says grandson Li Ravicz ’88.

Kallison, who died in 2004, posthumously joined the ranks of Sandra Day O’Connor, Patsy Cline, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Annie Oakley as an inductee into the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame. She’s the first Jewish woman to be inducted and the second Vassar graduate. (Rodeo photographer Louise Larocque Serpa ’46 was inducted in 1999.)

A third-generation Texan, Kallison initially wanted to work in finance, says her daughter, Frances “Bobbi” Kallison Ravicz ’60. The Great Depression put a halt to her plans. Instead, Kallison married Perry Kallison and, together, they managed their 2,700-acre Diamond K Ranch, where they bred and raised prize-winning Hereford cattle.

Though work on the ranch—including cooking for hundreds of World War II soldiers at USO BBQs the couple hosted—required plenty of effort, Kallison found time for her other pursuits, which Ravicz says, were many.

Her mother bred and rode palominos at the San Antonio ranch, eventually co-founding the Ladies’ Auxiliary to the Bexar County Sheriff’s Mounted Posse, a precision horseback riding and mounted drill team popular at rodeos, fairs, and parades. (The troupe even appeared in the John Wayne film Rio Grande. Its earnings were donated to a Texas children’s polio unit.)

Kallison’s sense of duty to her community was unwavering, Ravicz says—she championed causes wherever she noticed a need. When Kallison’s own mother took ill, she recognized a demand for caregivers to aid those bedridden at home and helped to establish the Visiting Nurse Service in the San Antonio area. Kallison co-founded the Happy Hour Nursery School, a preschool for blind children, and then successfully lobbied the state legislature to mainstream the children into public schools. Seeing some of the mothers of these children struggling to pay for school clothes and supplies, Ravicz says her mother personally talked with the owners of San Antonio department stores and convinced them to offer free back-to-school shopping trips for the families in need. Kallison led San Antonio’s National Council of Jewish Women to establish a prenatal clinic and well-baby clinic for the city’s poor and successfully lobbied to open a maternity ward at the public hospital. “She had a tremendous sense of duty,” Ravicz says. “She was just a very generous, very kind-hearted person.”

That benevolence extended to her service to other organizations, including the American Jewish Historical Society; the Texas Jewish Historical Society, which she founded; the San Antonio Museum Association; and the Witte Museum. Kallison also co-founded the San Antonio Botanical Center and Gardens. For her leadership roles at the Bexar County Historical Commission, she was honored with an appointment as Hidalgo de San Antonio de Béjar, an award typically bestowed upon the region’s most celebrated men, Ravicz says.

“She was very much respected and revered in what was a man’s world....When she walked into a room, she was a commanding presence.”

Kallison’s writing on Jewish history in the West—and Texas, in particular—was featured in scholarly journals. Her work was so stellar that Kallison was enlisted by the state’s governor to be the primary researcher for an exhibit on Jewish ethnicity at the 1968 World’s Fair in San Antonio; it eventually became a permanent exhibition at the Institute of Texan Cultures.

Granddaughter Elenita Ravicz ’84 says Kallison was aided by a fierce intelligence and a near-total recall for facts: names, dates, and other data.

“She had the most amazing memory of anybody that I’ve ever known. It wasn’t a photographic memory, but she could remember things from courses she had at Vassar in the 1920s better than I could remember classes that I’d had just a few years ago,” Ravicz says.

It’s Kallison’s hard work, perseverance, resilience, and independence—characteristics that helped shape the American West— that brought her to the attention of the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, says Bethany Dodson, the museum’s research and education manager. The organization celebrates individuals in various fields, including artists and writers, ranchers, entertainers, champions and competitive performers, trailblazers and pioneers, and women who contribute to the cowgirl legacy. Kallison’s accomplishments fall under many of those categories, a rarity, Dodson says.