Vassar Fights for the Women's Vote

Vassar alumnae/i and students are known for being politically active, whether they are voicing their opinions, getting out the vote, or even running for public office. But at the turn of the 20th century, the debate about whether women should be allowed to vote was an unwelcome conversation to some on campus.

According to the Vassar Encyclopedia, there was outright opposition to the idea of women voting from college president James Monroe Taylor, who held the office from 1886 to 1914. He felt that college was a place where women should “pursue their studies in disinterested tranquility, freed from demands for political or social commitment.” It’s said that he left his position because of “friction, suffrage, and socialism.”

Despite Taylor’s opposition, there were those on campus who supported suffrage. Professor Maria Mitchell, for example, was cited as a supporter in a Vassar Miscellany article from Dec. 1, 1889. The Vassar Encyclopedia mentions several other faculty members who were in favor of the vote—among them, Lucy Maynard Salmon, Laura Johnson Wylie, Gertrude Buck, and Herbert Elmer Mills.

In the 1890s, the Miscellany and other periodicals published articles detailing suffrage meetings in New York City and bits of news on the topic from other parts of the U.S. and England. One of the most prominent Vassar suffragettes was Harriot Stanton Blatch (1878), the daughter of pioneering suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Blatch began her work on women’s voting rights in the U.S. after living in England for 20 years. There she worked with the Women’s Franchise League, forming the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women to help recruit working-class women to the movement.

The New York Times reported that Blatch helped organize the 1912 New York City Suffrage Parade—a show of force with 20,000 women and children and 500 men in attendance. During the parade, Blatch donned a rose and gray cowl that signified her master’s degree from Vassar, the newspaper reported.

Shortly after the turn of the century, the suffrage movement took hold on campus; students and alumnae began to meet, march, and raise their voices in support of women’s voting rights.

The Vassar Encyclopedia noted that Inez Milholland (1909) first became involved in the movement after meeting suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (played by Meryl Streep ’71 in the 2015 film Suffragette) while attending high school in England.

In her junior year, Milholland, writing for the Miscellany, noted that the English suffragettes’ actions were a far cry above the “disappointing efforts of American women.” English suffragettes were protesting in public, getting arrested, and going on hunger strikes while in jail. Some groups, such as Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, became quite militant, disrupting government party meetings and destroying public property.

The passionate Milholland often clashed with Taylor. In one instance, the president forbid a lecture—organized by Milholland—by noted suffragist Jane Addams, who had already spoken at other women’s colleges, including Bryn Mawr, Smith, Wellesley, Radcliffe, and Mount Holyoke. And Taylor banned women’s suffrage meetings from campus.

Milholland was not to be deterred and in 1908 held a suffragette meeting in a cemetery adjacent to the college with students, alumnae, and others in attendance. The meeting—and Taylor’s ire over it—was reported in Woman’s Journal and the New York Times, the first of which noted that the meeting attendees included Blatch and Helen Hoy Greeley (1899), corporation counsel for the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women.

More off-campus meetings followed, and, by 1912, women’s suffrage meetings finally were permitted on campus. In 1914, the year Taylor left office, the board of trustees allowed the formation of the student Women’s Suffrage Club. Things seemed to be improving for the suffragettes. Incoming president Henry Noble MacCracken had stated his personal belief in women’s suffrage and was progressive in his academic policies. However, as the Vassar Encyclopedia noted, he denied attempts to have the more “radical” elements of the movement—such as Milholland—speak at Vassar.

Even after Milholland graduated and moved on to law school at New York University she continued to push for voting rights, most famously participating in the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 in Washington, DC, dressed in white, astride a white horse. She remained a staunch advocate until her death from anemia in 1916.

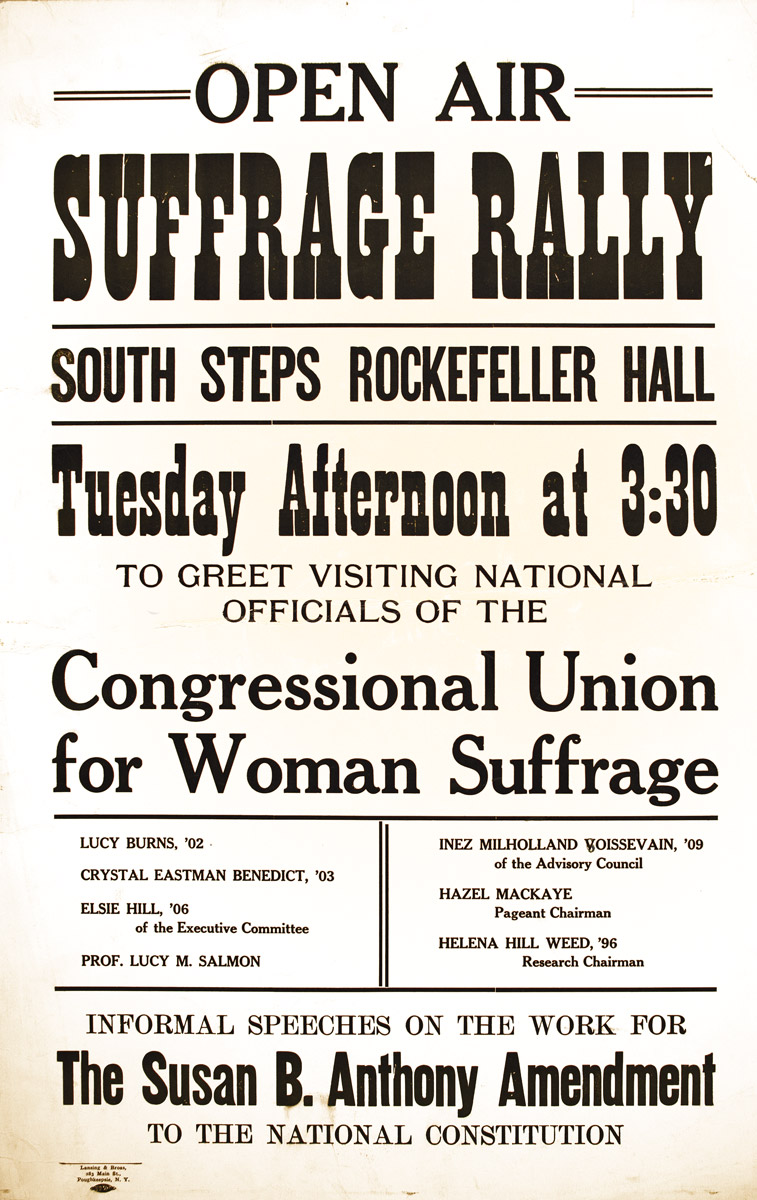

There are, of course, many more Vassar alumnae suffragettes. Though no complete list exists, the book Jailed for Freedom by Doris Stevens included the names of suffragettes arrested for picketing the White House in 1917, including Lucy Burns (1902), Gertrude Crocker (1907), Elsie Hill (1906), Florence Brewer Boeckel (1908), Elizabeth McShane Hilles (1913), and Martha Reed Shoemaker (1910).

Crystal Eastman (1903) was a feminist activist and civil rights advocate and had been since a young age. While there isn’t much written about her activism during her years at Vassar, Eastman was a recognized figure in the suffragette and workers’ rights movements after graduation. Also a graduate of NYU’s School of Law, Eastman co-founded the Congressional Union (it later became the National Women’s Party) with suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, and co-wrote an early attempt at a U.S. Equal Rights Amendment. After she was blacklisted during the first Red Scare—it was thought by government officials and others that she was a communist—she moved to London for several years for work with the socialist journal the Liberator, later returning to the U.S. a brief time before her death in 1928.

Vassar suffragettes endured arrests and bullying, and many never lived to see the federal government grant women the right to vote in 1920.

For women like Eastman, the war had just begun. In her famous speech, “Now We Can Begin,” given after ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Eastman said that men were likely happy the hullabaloo was over with. “But women, if I know them, are saying, ‘Now at last we can begin.’ In fighting for the right to vote, most women have tried to be either noncommittal or thoroughly respectable on every other subject,” Eastman noted. “Now they can say what they are really after; and what they are after, in common with all the rest of the struggling world, is freedom.”