Distracted Reading in the Digital Age

Most of us have been there: We're reading something we need to absorb, concentrating on the page, when we hear that familiar and often welcome sound. We have a text message. We look, naturally, and usually answer back and then return to reading. Soon enough we'll need a break from that and we check to see what's up with email, Twitter, Facebook. Oh, and then another text. We settle back in to finish the reading, which we do, more or less. But have we really grasped what we needed to? This scenario is undoubtedly played out among students in an even more intense way as they face dense reading for demanding courses. So how's this multitasking affecting learning?

Enter two likely investigators—a librarian and an English professor.

Ron Patkus, an adjunct associate professor of history and head of Vassar’s Special Collections, and Susan Zlotnick, an English professor and dean of freshmen, had been comparing notes on what they felt was less-than-ideal student engagement in Patkus’s 300-level Bible as Book and Zlotnick’s Nineteenth-Century British Novels courses.

In Gathering Voices, Vassar faculty’s online forum, the two recounted: “Since both of us teach rich, dense historical materials that require long stretches of concentration, we began to wonder whether the students’ unresponsiveness to assigned reading was just coincidence—classes have personalities—or whether we were witnessing some larger shift in the reading habits of our undergraduates, perhaps one brought on by their digital habits.”

They had both heard an NPR program about a study by Michigan State literature scholar Natalie Phillips, who collaborated with Stanford University neuroscientists to examine the effects various levels of reading have on the brain. Phillips’s subjects read a chapter of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park in two ways—first, browsing/pleasure reading, as one might do in a bookstore or surfing the web, and then with fixed attention—both while having their brains scanned in an MRI machine.

Phillips and her fellow researchers observed a global increase in blood flow to the brain during close reading, which, she says, suggests that “paying attention to literary texts requires the coordination of multiple complex cognitive functions.” Close reading, the researchers found, most activated parts of the brain that are associated with touch, movement, and spatial orien-tation. It was as though readers were actually experiencing being in the story.

“For those of us who are readers, we know what that means,” says Zlotnick. “Hours pass and you’re just completely in that world. In literature class, you take the emotional responses generated by deep reading and then move students into thinking about the structure of the text, the historical context, but you need that emotional response or else they’re not interested.”

“It’s a real question for people who teach books,” says Patkus. “Even if a student says they’ve read a book, have they really experienced it the way it’s meant to be experienced?”

At the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching conference held in May of 2013, Jennifer L. Roberts, the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities at the university, along with other presenters, was asked to explore the question: “In this time of disruption and innovation for universities, what are the essentials of good teaching and learning?” Her answer, though more eloquently presented, can be summed up in one word: Deceleration.

Harvard Magazine printed the adapted text of her talk, noting that though Roberts uses digital technology in her classes, she thinks it essential to offer students experience in “modes of attentive discipline.” One such experience is the assignment she gives all of her art history students. She asks them to write a detailed research paper based on a painting of their choice. That’s not unusual, but the stipulations are. Roberts said:

The first thing I ask them to do in the research process is to spend a painfully long time looking at that object. Say a student wanted to explore the work popularly known as Boy with a Squirrel, painted in Boston in 1765 by the young artist John Singleton Copley. Before doing any research in books or online, the student would first be expected to go to the Museum of Fine Arts [Boston], where it hangs, and spend three full hours looking at the painting, noting down his or her evolving observations as well as the questions and speculations that arise from those observations.

The students squirm at the thought of sitting—without distraction—for three hours straight, but Roberts reports that, as they undertake the assignment, they are astounded by the continual unfolding of observations as their minds slow down.

“What this exercise shows students is that just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it,” said Roberts. “Just because something is available instantly to vision does not mean that it is available instantly to consciousness. Or, in slightly more general terms: access is not synonymous with learning. What turns access into learning is time and strategic patience.”

It seems clear that a hyper-digital culture has fostered in students—indeed, in most of us—an expectation of immediacy, and, not least, the pressure to multitask. This has led to real difficulties in focusing, not just on art, but on long or complex printed works. This shift in reading habits is profoundly impacting the teaching of the liberal arts, where the ability to focus on lengthy texts, often in unfamiliar idioms, has long been a necessity.

After having informal conversations with other colleagues and researching the topic online, Patkus and Zlotnick found that distracted reading was a subject of interest to many academics. The topic found traction in two well-attended forums that included librarians and faculty members from across Vassar’s disciplines.

During those sessions, other faculty members confirmed what Patkus and Zlotnick had seen. Librarians also noted an increased tendency among students to multitask in the library (for example, checking their devices frequently while studying).

Patkus and Zlotnick say that faculty members came away from the two sessions not with a judgmental perspective on student behavior, but rather, with an acceptance that there is, indeed, a shifting culture of learning and that they must realign their pedagogies accordingly.

Last November, a conference at Vassar titled “Engaged and Active Reading,” sponsored by the Liberal Arts Consortium for Online Learning (LACOL), afforded the faculty the opportunity to broaden the conversation, to share the collective wisdom of LACOL’s eight member liberal arts colleges—Amherst, Carleton, Claremont McKenna, Haverford, Pomona, Swarthmore, Vassar, and Williams. (Other regional colleges such as SUNY New Paltz also participated.)

View the keynote presentation, "The Attentive Reader (and Other Mythical Beasts," by Alan Jacobs, Baylor University Distinguished Professor of the Humanities here.

In panel discussions, participants introduced the questions: What have we noticed about shifts in student reading? In what ways might we adapt our pedagogy to the realities of the digital age? What new strategies are needed to encourage a deeper engagement in reading?

What are we noticing?

As dean of freshmen, Zlotnick says she often asks incoming students whether they were readers in high school. Many say no. “When I was in high school, all I did was read. There was nothing else to do!” she jokes.

The absence of a “reading practice” doesn’t bode well for students’ ability to focus on complex reading tasks. Tom Olsen, associate professor of English at SUNY New Paltz, who served on the panel “Where Are Our Students Now?” says, “If you teach Shakespeare,” which he does, “you’re always up against a reading comprehension problem, always up against archaic, difficult, dense language.”

He began to split assignments in half, refrain from assigning whole plays, and design lectures around individual passages.

Olsen attributes the shortening of attention spans to the “fear of missing out.” He says, “The idea of sitting for two hours in a library carrel without glancing at the phone or wondering what’s coming through on email or social media has fallen by the wayside. Slow, steady concentrated reading has suffered. It’s a daily, lived experience for everyone, but I think it’s more acute for people in that 20-something age group. Our cognitive capacity has changed to accommodate the technology that has put wonderful things in front of us, but it comes at some cost.”

The difference, he says, is that students tend not to see the “costs.” Last fall, Olsen taught the senior seminar From Gutenberg to Google Books, which, in part, examined the “reading habits and the economics of publishing in the digital age.” Olsen says that over the course of the semester, he learned a lot from his students about how they view these issues. He says, “They understand that the inability to do deep reading is a widespread social problem, but they don’t think it affects them. Maybe one day brain science will tell us that our brains can adapt to a much more cluttered and distracting reading environment and do fine, but I think the majority of the research is not pointing that way at all.”

In a 2009 study, published in the journal Computers & Education (Vol. 54, Issue 2, May 2014), researchers from the Central Connecticut State University tested the effects of instant messaging on reading comprehension. They had one group of students read and respond to instant messages (IMs) while reading an online textbook; another received an IM before reading, but not during; and another read the textbook without interruption. Researchers tracked the time it took for each student to read the passage, and then tested their understanding of what they read.

They found that students who were interrupted by IMs would take significantly longer to read the passage and performed more poorly on a test of their understanding than the other two groups, even after the time it took to read and send the IMs was subtracted. “Our findings suggest that they will actually need more time to achieve the same level of performance on an academic task,” the researchers noted.

So how do faculty members get students to focus? Several panelists advocated using the very technologies that are seen as “distracting” to increase student engagement.

Digital Annotation

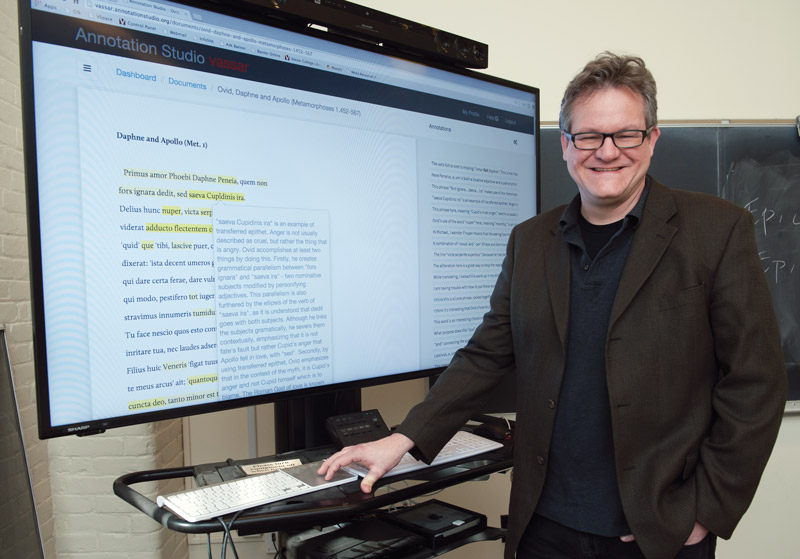

Bert Lott, professor of Greek and Roman studies, who served as a panelist in the session titled “Technologies for Engaged and Active Reading,” says, “In teaching ancient languages, we used to rely on a deep investigation of grammar, syntax, and lexicography to slow students down as they read the text; it made them engage on a word-by-word basis. Electronic tools have done away with that mode of slowing students down. For good or ill, you can go straight online to get that information very easily.”

He needed to find another way to engage students.

What he discovered was Annotation Studio, a product that grew out of MIT’s HyperStudio, which explores the “potential of new media technologies for the enhancement of education and research in the humanities.” Annotation Studio—created by lead programmer and Vassar alumnus Jamie Folsom ’92—allows students to make digital annotations to words, phrases, or sentences within a given text and to comment on some aspect they find of interest. Or they may ask questions. Annotations appear alongside the text, and fellow students and Lott can then respond.

“I require students to examine the text before and after class,” says Lott. “They write annotations about grammar, syntax, and lexicography and compose interpretive comments. Strands of conversation emerge between students as they do it.”

Lott says there are many benefits of this approach, in addition to encouraging students to more deeply examine the text. “Having students write down their grammar questions carefully and ask them before class adds elements of the ‘flipped classroom,’ ” he says. “It allows us to get those technical questions answered outside of class, so the expectations for what they know in class are higher. It allows them to formulate their thoughts better and to participate more fully in class discussion because they have thought through some of their ideas beforehand.”

Moreover, he says, a closer examination of the text allows students to broaden their perspective on the work. “It frees them from thinking they have to believe what the text says at every point,” he reports. “They see their own ideas and their classmates’ right beside the text we are reading. It gives them visual encouragement that they are participants in making meaning out of the text.

Seeing what such technologies can bring to the classroom, Lott says he’s “not entirely sympathetic to the notion that distracted reading and devices are wholly bad, that our job should be to protect the classroom as a space for only the old kind of reading. It’s much more complex than that.”

“I think this is going to be the way in which students are going to engage and get information. Technologically enhanced reading can have huge benefits to education and scholarship. We’re just not sure what they are or we’re not entirely convinced of them yet,” he says. “This is one way for my students and me to practice what it means to read texts in the form they will undoubtedly read them as their lives move on.”

Scaffolded Reading

In 2014, Zlotnick executed a grand experiment in supportive or “scaffolded” reading as part of the college’s annual freshman common reading project. It was a tremendous success.

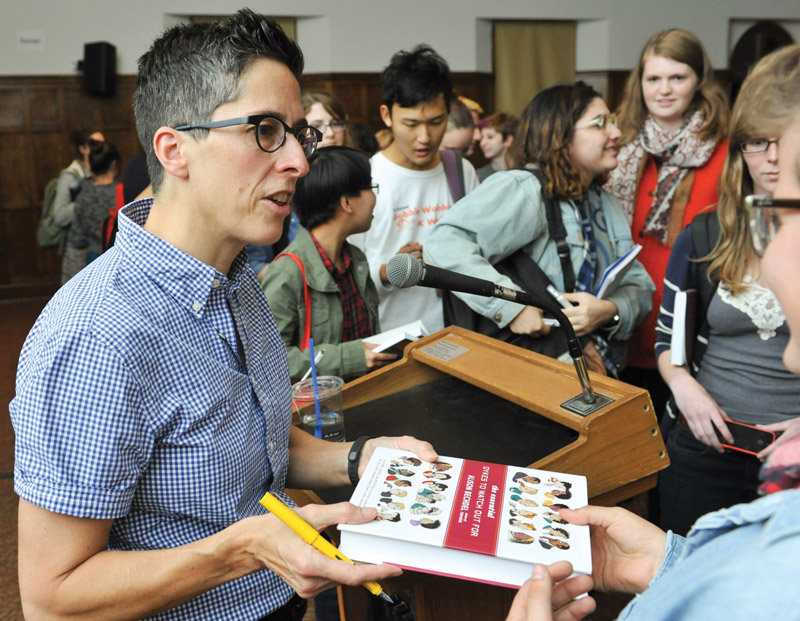

Alison Bechdel’s groundbreaking graphic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic was chosen as the freshman common reading for Vassar’s class of 2018. Traditionally, the college sends members of the incoming class the freshman reading selection over the summer. It’s up to faculty members to decide whether to use the reading in class during the fall semester. The book’s author then presents the William Starr Distinguished Lecture, entertaining questions and comments from students.

Last year, Zlotnick decided to try something different.

Over the summer, incoming freshmen were enrolled in a Moodle (a commonly used, interactive online learning platform), where they shared their responses to Bechdel’s coming-of-age and coming-out story. Students were also asked to view three videotaped lectures and respond to a series of questions and prompts offered at the end of each presentation. One video featured English professor Peter Antelyes, who teaches courses on graphic literature; among other requests, Antelyes asked students to submit a cartoon or other drawing in response to Bechdel’s work. German studies professor Jeff Schneider examined the memoir as a queer text. And reference librarian Gretchen Lieb offered library resources related to the reading.

Out of 665 members of the Class of 2018, almost 430 students posted to the Moodle, making a total of 1,273 entries. The videos were viewed a total of 1,328 times by incoming students in the U.S. and 16 other countries. And 43 students uploaded drawings in response to Antelyes’s request.

In her presentation on the LACOL conference panel “Technologies for Engaged and Active Reading,” Zlotnick said the intellectual scaffolding vastly improved the quality of the students’ responses.

“The combination of videotaped lectures, supplemental readings and videos, and focused but varied questions that pushed the students to think critically and creatively led to more careful reading on the part of the incoming freshmen,” she said. “The multidisciplinary nature of the summer Moodle—three videos from three different disciplinary perspectives—also usefully underscored for the students that there are many different ways of entering a text. The high quality and high seriousness of all three video ‘lectures’ broadcast to our students the profound differences between high school and college teaching. Moreover, because the first video focused on how to approach a graphic work formally (by focusing on its formal qualities, on the interaction between images and words), it modeled for our students attentive reading.”

When Bechdel finally presented her lecture in the Villard Room this past October, the audience was standing-room-only. Dean of Faculty Jonathan Chenette says that was quite a feat, since over the last few years, the freshman reading has seemed “decreasingly relevant to today’s students.”

Chenette says he could see the LACOL conference attendees’ eyes light up when Zlotnick described the program. “It not only provided a model for other LACOL colleges to follow,” he says, “but more important, it reinvigorated reading. The social aspect of it created excitement and enriched the depth of and engagement with the the experience.”

Building a Reading Culture

Patkus says that during both faculty conversations and the conference a number of other ideas emerged about creating more of a campus culture around reading. “It may be carving out quieter spaces on campuses specifically dedicated to reading—a reading lab, for example. Or having readings in the library during study break. It’s probably not going to be just one thing,” he says.

Last year, the Vassar Libraries participated in the American Library Association’s Banned Books Week. Reading salons focusing on such previously contraband works as Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings were set up in locations across campus, including residence halls. One of the most well-attended events was Banned Books Karaoke, hosted by Banned Books co-organizer Matt Schultz, a house fellow in Jewett and director of Vassar’s Writing Center. More than 100 people came to watch students read passages from some of the “most-banned” books in history.

Lieb, one of the organizers of Vassar’s Banned Books events, says the activities were as much about “promoting reading for the sake of reading” as they were about raising awareness of the contested books.

Buoyed by Banned Books’ popularity, Schultz has continued to organize reading salons in the residence halls, and Lieb says she’d like to see the library positioned as a space for reading again. “Students need a designated space where they can slow down, where they can engage in ‘slow reading,’ ” she says. “Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a movement for reading like there was for ‘slow food’?”

Which brings us back to patience. It’s clear to see that even if we accept the role that technology is playing in all of our lives, that cultivating the kind of patience necessary for “close reading” will enhance a variety of areas of study—from art history to chemistry.

Why is this so important? Zlotnick says, “We all read Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid for the first Vassar faculty conversation. She talks about the fact that reading—when you are quietly attentive to a text and you are alone with your own thoughts—encourages reflective habits of mind. That’s key to what we understand as the liberal arts graduate. Someone who is thoughtful and reflective, who can think, not just about ideas, but about his or her own ideas and reflect upon them.”