Framing History

Those topics are presented in two new publications: English professor Donald Foster is the editor of a vour-volume collection of women's writing spanning 750 years. And history professor Nancy Bisaha and Robert Brown, professor of Greek and Roman Studies, are credited with the first English translation of a gossipy 15-th century Latin text by Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II).

Women’s Work

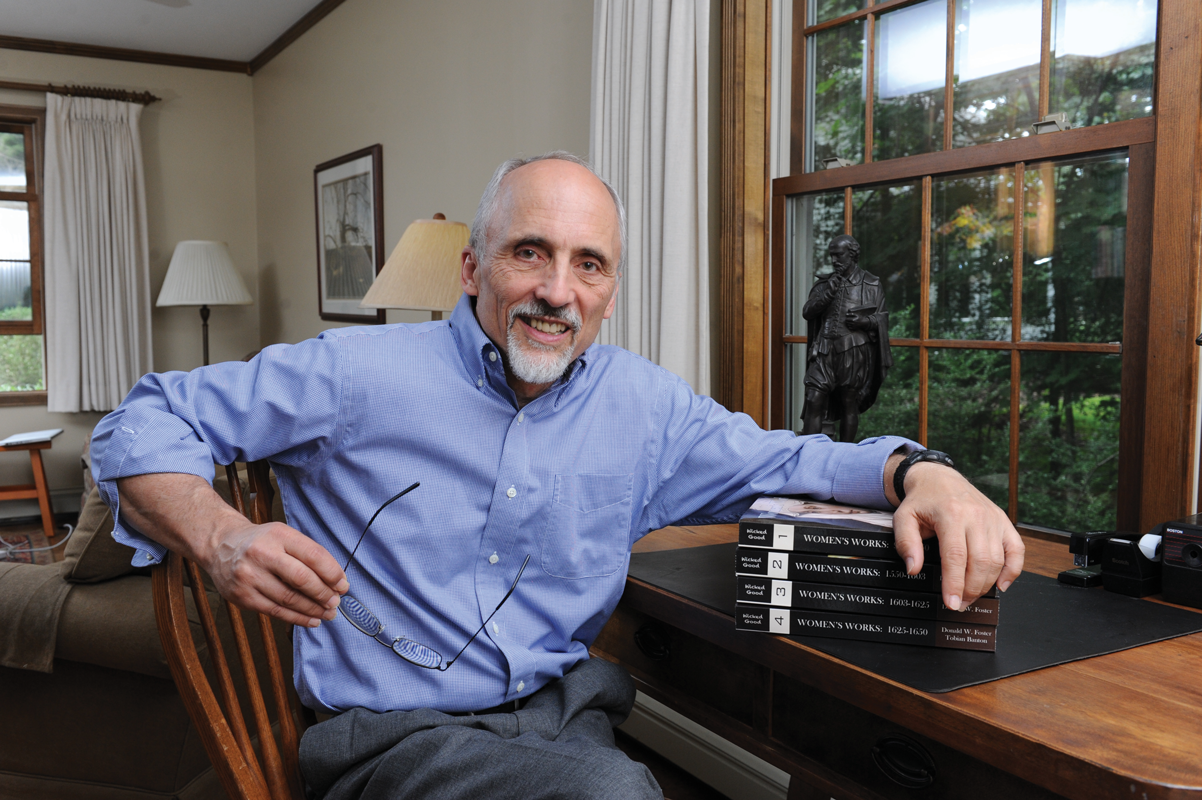

Though marginalized, treated as property, left uneducated, and harassed for simply being born female, women still found a way to create a voice for themselves through the centuries. Earlier this year, English professor Donald Foster published his new four-volume work, Women’s Works, as a definitive place to read, study, and learn about the voices of women who lived between 900 and 1650.

Foster published the collection of women’s writings after nearly 30 years of research. The book includes poems, letters, manuscripts, songs, and narratives, as well as biographies. Each volume covers specific decades, and two volumes are based entirely on the first half of the 17th century.

“It was partly coming to Vassar (in 1986) that got me interested in early women’s culture because we had such a rich tradition here of women’s learning and women’s education,” Foster says.

Starting in the mid-1980s, Foster researched, wrote, and edited Women’s Works, sometimes putting it on a back shelf to concentrate on other projects. The past four years, with the assistance of Tobian Banton ’12, Foster mounted a full-court press to get the collection published, he says.

His research—in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the U.S.—brought forth swells of information on women’s writings throughout the centuries. He didn’t know at the beginning of his research that his work would span four volumes, but it soon became obvious that there were many women writers he wanted to include.

“I think anyone who reads all the way through even one of these volumes would understand something about how tough it was for women and how remarkable these women were. They rose past the obstacles that their culture threw in their way and left their mark in one way or another,” Foster says.

In many cases, the stories, songs, and letters are sad—there are tales of abusive marriages, unrequited love, and lives lost to political violence or the ambitions of fathers and husbands.

One example is Lady Jane Grey, whose short and fraught life is detailed through her correspondence with family members and a detailed biography. At the age of 16, Grey was considered one of England’s most promising scholars, Foster writes. She was fluent in classical literature, the Romance languages, prose rhetoric, and Protestant theology. At age 17, she was beheaded, the victim of her father’s attempt to place her on the English throne instead of Princess Mary, the eldest daughter of King Henry VIII.

In other cases, especially in the 1600s, women found themselves in new roles, helping to create political discourse and a space of their own.

Margaret Cunningham wrote about the abuse and financial neglect she suffered at the hands of her husband, James Hamilton. In 1606, she sued him for a guaranteed annuity to live on after he left her destitute with five children. Later, in 1610, Cunningham requested and was granted a divorce—a rare and historic action in those days.

“Women actually played a bigger role in 17th century politics than you would think,” Foster says. “Women were a driving force for democracy, a new idea in the 17th century. Women by the thousands petitioned the government for social and economic reform, and during the English Civil War, women demonstrated in the streets, demanding peace. I learned so much from the project.”

Translating Europa

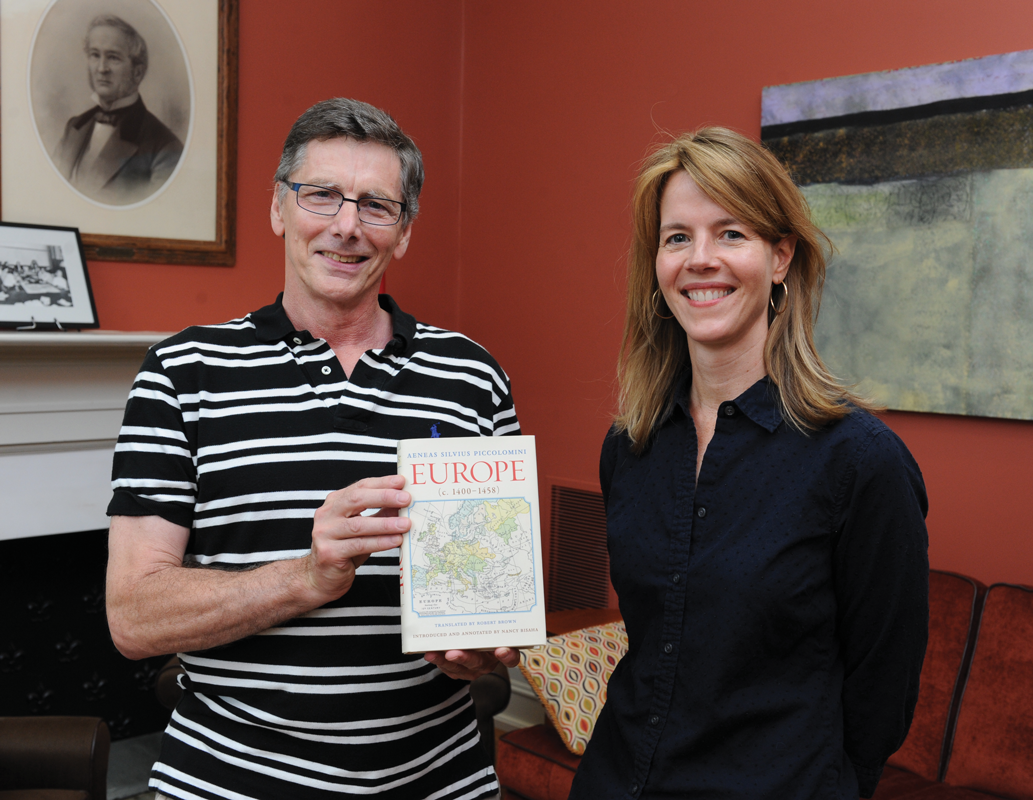

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II) had an interesting way of framing history. The author of several books, Piccolomini used his position to shed light on some of the juicier tidbits of 15th-century Europe.

Nancy Bisaha, history professor and department chairperson, describes Piccolomini’s book Europa as “a history of recent events, in his own time, from roughly 1400 to 1458. He goes all over the map, country by country, and talks about some of the events that he felt were interesting,” she says.

What Europa didn’t have, however, was an English translation.

Bisaha, an expert on the Renaissance period, first began work on the translation in 2008, and soon joined forces with Latinist and professor of Greek and Roman Studies Robert Brown.

The duo discovered that intensive research would be required because Piccolomini frequently remarked on historical events without including proper names, dates, locations, or context.

“I ended up writing to several scholars who work in the field and asking if they could read over passages, or if they had any idea what he was talking about in a few puzzling instances. There was a lot of detective work,” Bisaha says.

Brown says, “As a classicist, I specialize in Latin texts from about 100 BCE to 100 CE, so it was a challenge to tackle a work from the 15th century, especially one so ambitious as Piccolomini’s Europa.” He started his translation “cold,” without any knowledge of Piccolomini or his historical context. “It felt like traveling though an alien land,” he recalls.

With the help of Bisaha, he says, he gained greater knowledge of the background needed for the translation.

Together, the two uncovered a treasure trove of personal information about historical figures of the day.

Piccolomini had been a secretary at the Imperial Court, which made him privy to a great deal of information coming in from the court’s ambassadors and visitors.

“Europa has a gossipy feel at times,” Bisaha says. “He tells stories about rulers from a very intimate perspective. The Duke of Milan, for example, was afraid of thunder. The rulers of Lithuania had an alleged fondness for bears—one supposedly used them for executions and another kept one as a pet who roamed the palace. The Duchess of Carinthia locked up her drunken, slovenly, tyrannical husband not once, but twice, prompting Aeneas to call her ‘a woman of outstanding beauty and more than a man’s audacity.’”

Readers also learn about the Count of Armagnac who “was stricken with an incestuous passion for his sister and had the temerity to seek a papal dispensation to marry her,” says Bisaha. “This request was, fortunately, denied.”

Published last year, the new book offers readers a chance to learn about history in a new way.

“In a sense, Piccolomini helped shrink the borders of Europe by giving us that insider feel to every place he treats,” Bisaha says. “Whether it’s folk tales or intimate stories about rulers, comments on the census, or how they’re building boats for an expedition, he provides these nice anecdotes that really add texture.”