Life Studies

The men in the portraits are smiling. Painter Peter Charlap has pictured all five of them posing with things they enjoy: books, origami, a chess set. They are all prisoners on death row. Four years ago, the Vassar professor tuned his car radio to an interview with appellate lawyer David R. Dow, who was describing his work with inmates at Texas’s infamous Polunsky Unit state prison. Because Charlap commutes between the signals of two local NPR affiliates, he heard the interview twice. “The first time I was very moved by it,” he recalls. The second time, he thought, “I have to do something.”

Charlap was hit hardest by Dow’s comments about one of his clients who was executed after more than a decade on death row. “He was simply not remotely the same person he’d been when this crime was committed,” Dow told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross. “I would have had no hesitation asking him to babysit my infant son.”

“I don’t think I’d ever thought too much about death row, or the people on death row,” Charlap admits over coffee in an upstairs office in Taylor Hall. “But it struck me as such a waste of human life.”

The urge to “do something” swirled in his head for weeks. He’d recently seen an exhibit of portraits by Flemish master Jan Gossaert at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and got the idea of painting portraits of men on death row. “If people could actually look at these guys and see them, it might change the way they think,” he explains.

Charlap’s wife, an attorney, cautioned him to think about the emotional commitment he would be making. Did he really want to travel to Texas and get to know people who would likely be executed?

He did.

Charlap wrote to Dow, who was intrigued by the project and offered to put him in touch with several inmates. He wrote first to Christopher Anthony Young and received an enthusiastic reply. A research grant from Vassar provided funding for eight trips over a two-year period, and Charlap began the long process of securing permission from prison authorities.

“It’s very bureaucratic—you have to be placed on a special visitors list,” he explains. Because his driver’s license listed a PO box instead of a street address, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice took an extra month to approve his request.

The Polunsky Unit is in Livingston, Texas, about 60 miles north of Houston. Entering the facility for the first time was an education. “They search your car before you park, then you go through security. It’s like getting on an airplane. You have to remove your belt and shoes, and they physically frisk you—they ask you to lift your feet to make sure there’s nothing taped underneath.”

The visiting area has about 30 booths. “The guys are behind glass; you talk on phones,” he reports. “The big activity is going to the vending machines. You can carry in $25 worth of coins in a transparent baggie to buy snacks from the machines. It’s terrible, the kind of food you’d find in a gas station, but the guys all say, ‘It’s so much better than what they feed us.’ It’s like sharing a meal.”

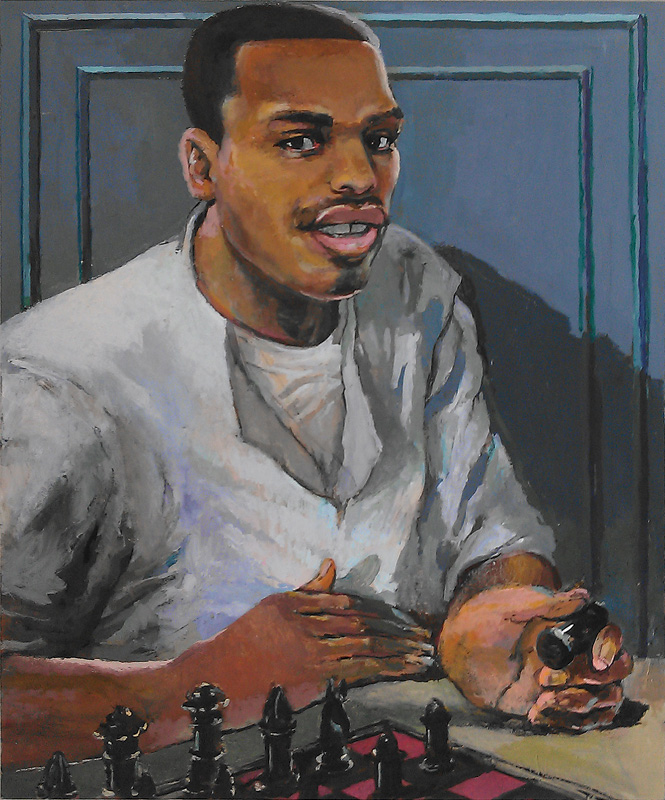

Charlap’s first encounter with Young was “very emotional. I was holding back tears,” he says. “Sitting down with somebody I didn’t know, and with whom I probably share no common experience” felt awkward at first, but they quickly found ways to connect. “Chris is very bright—if his life experience had been different, he would have gone to an Ivy League school. I asked him what his dreams were like, and he answered, ‘Have you ever read Carl Jung?’ This is a guy who only went through the eighth grade. He reads constantly and he’s an avid chess player.”

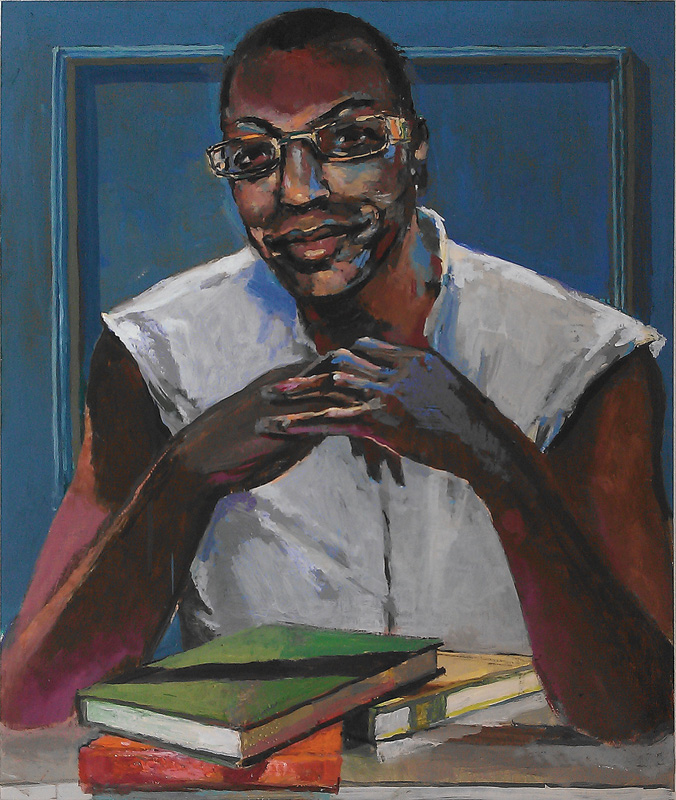

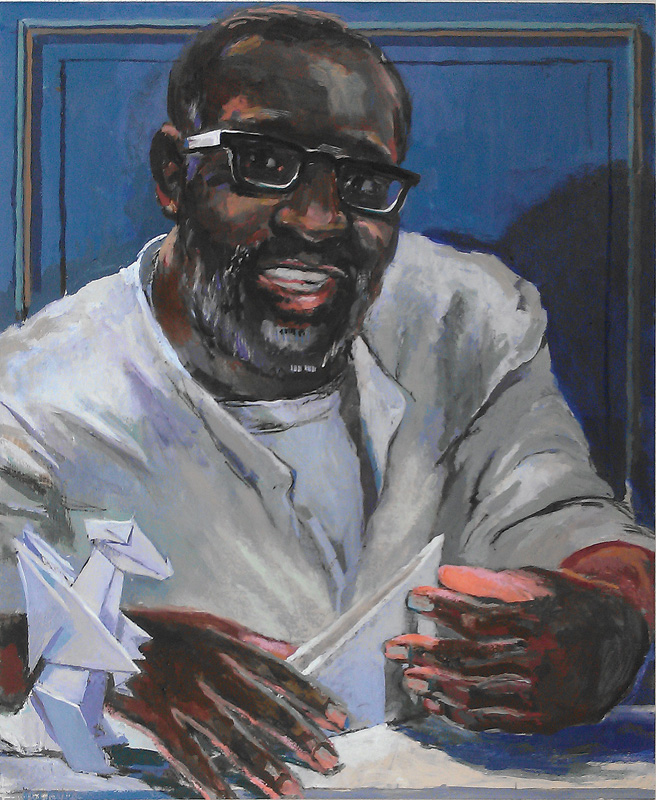

Prison rules prohibited Charlap from bringing a pen, pad, or camera, so he learned to rely on careful observation. “As soon as I finished my visits I’d go back to my hotel room to make sketches. I couldn’t work from life, so memory became a really important part of it,” he says. He also had access to press photos, mug shots, and snapshots taken by the prison guards, but Charlap found those images conveyed “nothing of their essence.” He did rely on photos for his portrait of Young’s friend and mentor Reginald Blanton, who was executed in 2009. For the rest, Charlap brought his hotel sketchbooks back to his studio in Stanfordville, NY, where he made larger drawings before starting to paint. He worked on each portrait for up to three years, repainting frequently “until I felt like when I looked at the painting, it was like being with the person.”

“The initial shock of Charlap’s death row portraits is their impression of normalcy,” Red Hook, NY, painter and critic John A. Parks writes in a brochure describing the Death Row Portrait Project. “They act as monuments to the human spirit as well as tender and thoughtful records of the individuals involved. They accord their subjects dignity and respect as fellow human beings in a way that perhaps no other art could achieve. This accomplishment raises a distinct disquiet in the viewer because, in the end, we are all members of a society that has decided to kill these people.”

The vast majority of the nearly 300 death row inmates in Texas are African American. Many received death sentences in their teens and early twenties.

Charlap is creating a brochure he hopes will inspire other artists, from Texas and elsewhere, to make additional portraits for an ongoing series that will tour the country, raising public consciousness. For now, all five paintings reside in his studio, alongside landscapes, automotive drawings, and decorated toy train tunnels he’s painted during his long career.

“I was always one of those kids who drew,” says the artist, who grew up in Westchester County, NY. Left-handed and slightly dyslexic, he was sent to a reading specialist in elementary school, an experience that he says, ruefully, “makes you doubt your intelligence.”

Nevertheless, as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, he pursued both pre-med and literature majors. Studio art wasn’t even listed in the catalogue, but he “sort of stumbled on the studios.” Eventually he switched into a BFA program, with an eye toward industrial design. “I didn’t know you could actually grow up and become an artist,” he says, though his relatives include a Philadelphia painter and several well-known musicians, including Morris “Moose” Charlap, one of the composers of Peter Pan, and jazz pianist Bill Charlap.

After Penn, Charlap taught art at the Choate School, then attended graduate school at Yale. Next he taught at Cooper Union, coming to Vassar in 1979. “It seems like a million years ago,” he says with a grin. “When I got hired, the studio art program was a tiny offshoot of art history. There was no major. Classes met once a week.” The dean of faculty called Charlap into his office, charging him with designing a studio art major. He chaired Vassar’s art department from 1993 to 1996, and will soon resume that position.

There are many things Charlap strives to impart to his students. “I try to get them to take drawing seriously, and to be willing to make changes in their work. The accidents that happen when you change something are often the most interesting. You can make a painting that’s smarter than you are—it’s a dialogue between you and the painting.”

His dialogue with the prison portraits is ongoing and he’s hoping his brochure about the Death Row Portrait Project will have the intended effect.

Charlap’s feelings about capital punishment are unambivalent: “Any process that’s open to errors should not have the death penalty at the end of it.” (A second subject, Robert Garza, was executed last year. Eugene Broxton, Will Speer, and Chris Young remain in a holding pattern as their appeals crawl through the court system.) But his portraits don’t pass judgment. “I never wanted to focus on their guilt or innocence,” he asserts. “It’s more about saying, these are people.”

This may be one reason he chose to paint not just faces, but torsos and hands. “I’m interested in what hands do. Eugene [Broxton] does origami—when I showed that, I got his essence right away.” Another inmate, Speer, asked to be painted wearing a Star of David on a neck chain. When Charlap first contacted him, Speer was wary of outside visitors, saying, “I’ve been Bible-thumped black and blue.” But as they spoke, the men on either side of the glass realized they both self-identified as Jewish.

All five inmates he’s painted learned new things while incarcerated—yoga, meditation, reading—even though all death row inmates at Polunsky are kept in solitary confinement. They can’t see one another, and they can speak only to the men in cells immediately adjacent to theirs. They’re strip-searched by guards before and after they shower and are awakened at 3:30 a.m. for breakfast, delivered through a “bean slot” in the cell door.

Charlap looks out the window. The campus is starting to emerge from a long, harsh winter, and unlike the men he’s been painting, he is free to go outdoors and walk on new grass. “If my project could do even one tiny thing, it’s that they would treat them a little bit better,” he says.

In the office next door, a framed drawing of Young smiles down from the wall. Its message could not be simpler or more essential: I’m human.

Nina Shengold is a writer whose books include River of Words: Portraits of Hudson Valley Writers, with photographer Jennifer May, and the novel Clearcut. She won the Writers Guild Award for her teleplay Labor of Love. She is books editor at Chronogram magazine.