Vassar's Culinary Ambassador

Penelope Fexas Casas ’65 got into the professional world of food by writing letters and sticking her neck out. Beginning in the early 1970s, whenever the New York Times published an article on Spanish food, she wrote a letter in response. The Dining editor at that time was the influential Craig Claiborne, and one of Casas’s letters, about anguillas (baby eels), caught his eye. He got in touch with her, and she screwed up enough courage to invite him to dinner. Claiborne was so impressed by her cooking that he wrote an article about her “fabulous food” and then introduced her to Judith Jones, Julia Child’s legendary editor at Alfred A. Knopf. Jones offered Casas a contract for her first book, The Foods and Wines of Spain, which was published in 1982.

Through that book and those that followed, Casas has brought the exquisite cuisine of that country into countless homes. It is difficult to overestimate the impact of her work; thanks to Casas, once-unfamiliar foods like paella and tapas are now household words. Perhaps even more important, she always places her recipes within the context of history and culture, digging deep into the stories and techniques underlying each dish. She has taught many Americans about Spain’s diverse culinary cultures.

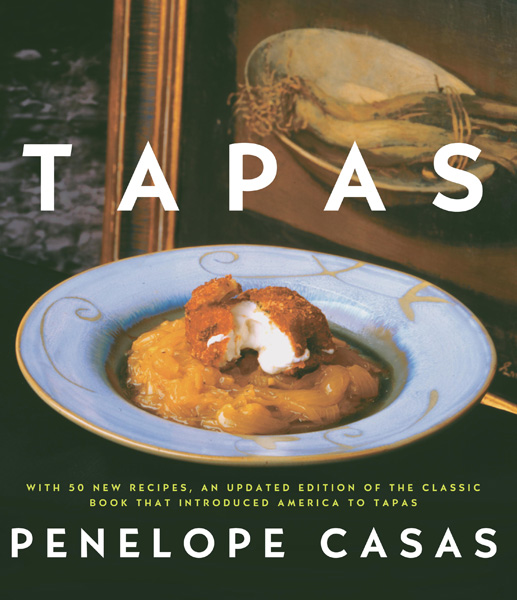

I am one of them. In the 1990s, while packing for one of my first extended stays in Spain, I had some hard choices to make. With little room in my suitcase, I couldn’t bring many books, so I settled on two I was sure I would use. The first was a book on Madrid, the second Penelope Casas’s Tapas: The Little Dishes of Spain, in its original 1985 edition from Alfred A. Knopf. As a professor of Spanish, I already knew a lot about Spain, but I also knew my limitations. The country’s culinary tradition of small dishes was so vast in style and vocabulary that I needed a knowledgeable guide. In those pre-smartphone days I kept the book close by my side to help me navigate the myriad ingredients of Spain’s famous small plates. Casas proved to be an expert guide. Her book taught me not only about the wonderful diversity of tapas, but also about Spanish culture—its customs and nuances.

As an undergraduate Spanish major at Vassar, Casas was already “involved with Spain,” as she puts it. But it wasn’t until she first traveled there in 1962 that she discovered the wealth of Spain’s culinary traditions, traditions largely unknown to Americans at that time. When her first book appeared, Spanish cuisine was still so uncharted in the United States that the jacket copy needed to explain just what it was: “You have only to sample a few of Penelope Casas’s more than 400 superb recipes to discover what Spanish (not to be confused with Spanish-American) cooking has to offer.” Americans’ lack of awareness of Peninsular Spanish culture and its food was, perhaps, not so surprising, given how closed the country was until Generalissimo Franco’s death in 1975. Casas’s task was monumental.

In her preface, she worked hard to dispel Americans’ prevailing misconceptions about Spanish food—that it is hot and spicy, for instance, and that tamales and tacos are “Spanish” cuisine. As the book unfolds, Casas reveals the rich variety of Spanish preparation methods and cooking techniques, always accompanying the instructions with anecdotes and cultural facts that add meaningful context. I can only imagine how surprising this book must have seemed to many Americans at the time. Yet they were obviously excited to make room for it on their bookshelves—after 30 years this seminal book is still in print.

Casas followed this groundbreaking work with several other equally accessible and informative cookbooks that deepened Americans’ understanding of Spain’s culinary culture. Along the way she also contributed articles to the New York Times, Gourmet, Saveur, and Bon Appétit, all of which helped raise readers’ awareness of the range of styles and possibilities offered by Spanish cuisine. In her articles and books she takes us into the kitchens of relatives and friends, into small bars, posh restaurants, and monasteries with unique recipes. She takes us along the paths of her extensive travels throughout Spain, always accompanied by her Spaniard husband, Luis. Through their culinary adventures she teaches us vital lessons about Spain.

She illuminates, for example, the powerful role that Spain’s politics, languages, history, and cuisine play in regional identity. The word “Spain” suggests, rather misleadingly, a uniform identity and culture. Although it is the country’s official designation, this name masks Spain’s regional distinctiveness, which is extraordinarily strong and a fundamental aspect of the country’s character. In ¡Delicioso! The Regional Cooking of Spain (Alfred A. Knopf, 1996) Casas explains this essential dimension by walking us through family recipes, variations on traditional dishes, and historical facts to show just how rooted Spanish dishes are in their specific geographical location. We visit coastal and interior Spain, Catalunya, Andalucía, and the Canary Islands, learning about local seafood and distinctive pastries, fried foods, and gazpachos. By organizing the book according to ingredients and different types of preparations (“Sauces,” “Peppers,” “Rices,” “Casseroles”), Casas effectively reorganizes our rudimentary understanding of each of Spain’s regions into something far richer and more nuanced, and invites us to consider the importance of culinary tradition in shaping regional identity.

As she says in Paella! Spectacular Rice Dishes from Spain (Henry Holt and Company, 1999), presenting Spain to non-Spaniards has often been an “uphill battle.” In writing the book, devoted entirely to the great Spanish rice dish, she was determined to correct misconceptions. After all, if there is one Spanish dish most non-Spaniards are likely to know, it is paella. Yet, according to Casas, this is the dish that has suffered the most outside of Spain, with little understanding of how the flavors of the rice and seafood or meat should blend. After experiencing too many poor translations—pots of gloppy Uncle Ben’s rice topped unimaginatively with chicken and lobster and laden with excessive garnishes—Casas’s daughter, Elisa, begged her mother to write this book to set the record straight on one of her own favorite dishes.

Casas makes it her duty to address such “horrors” by explaining first what paella is not: it is not a single, standardized dish; it is not difficult to make; and it is not time-consuming. You do not need expensive or specialized utensils. Once she has cleared these misconceptions, she shows us the vibrancy and depth of this dish by offering 60 different recipes gathered from her extensive travels, from favorite restaurants, and from hours of work in her own kitchen. Casas guides us in choosing the right type of rice to use, and shows us how to highlight each ingredient. In the process, she underscores the importance of regional takes on the dish. The final chapter of this book is a particular treat. Here, she presents an array of tapas and first courses to prepare in advance, so that when you are ready to make paella you can focus on your main task. This chapter is characteristic of Casas’s understanding of the simple yet intelligent ways in which ingredients and courses work together on the Spanish table.

When I asked Casas to recommend a recipe from one of her many fine books, she immediately recalled garlic shrimp, a classic tapas dish. “When I first got to Spain,” she told me, “it was like a revelation of taste to me. I remember how just a simple tapa like gambas al ajillo really stood out.” I can imagine the sense of revelation she must have felt visiting Spain at a time when its cuisine was virtually unknown to the rest of the world. In gambas al ajillo you have just three basic ingredients, free from heavy sauces and elaborate preparation, perfect for both whetting and satisfying the appetite. This sizzling, vibrant dish of shrimp, garlic, and olive oil opened the young Vassar student’s senses to a new way of understanding food.

Tapas, in particular, captured Casas’s imagination because of their novelty and range and the eating culture that underlies them (if we go bar-hopping in the States, then in Spain they “go for tapas”). Tapas, she contends, maintains its vital place in Spanish culture, even as there is a wave of ascendancy for Spanish cuisine. Cosmopolitan Americans are growing increasingly familiar with the foods of Spain, for example, and the world-famous chef Ferran Adrià owns the Michelin-rated elBulli, a restaurant on the Costa Brava considered one of the best restaurants in the world.

Casas’s books speak to the novice and the expert alike. Those who do not know Spain get lessons on food, culture, and the wide range of Spanish identities, while those of us who have lived and traveled in Spain can still learn from her tireless efforts to translate Spanish food to Americans.

To my delight, Casas told me that she’s completing a book titled 1,000 Spanish Recipes that pays even closer attention to regional methods and recipes. It will be the “inclusive reference for Spanish cuisine,” she says. I know I’m not the only one who impatiently awaits this volume. Even though Spain is much better known today than it was when Knopf published Casas’s first work, there is still much to say about its food culture. With Penelope Casas as our guide, we can happily continue the journey.

Leyla Rouhi is the John B. McCoy and John T. McCoy Professor of Romance Languages at Williams College, and director of Williams’ Oakley Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Editorial Note:

About a month after the "EAT" issue of the Vassar Quarterly [Spring-Summer 2013] was published, Penelope Casas lost her battle with a long illness. We feel grateful for the opportunity to honor the work of this remarkable "culinary ambassador."