Finding Roots

Had Nicole Sierra-Rolet ’84 followed the course of a carefully planned life map, she might have missed her calling among the enchanting vineyards and mountains of Vaucluse in southern France.

Schooled at French lycées in New York and Milan, her youth was circumscribed by the methodical Gallic approach to learning. It was only when her American mother urged her to attend a liberal arts college that everything was transformed for Nicole. “Vassar opened up a completely different way of looking at the world,” she says. “I could be creative and analytical at the same time.”

After college, Nicole found herself working in think tanks and finance, until she decided to chart a new course with her husband, Xavier, who had found and purchased a vineyard on an isolated mountaintop in the South of France.

The overgrown ninth-century priory and its grounds offered a sprawling, unspoiled site—one that needed vast amounts of work. But Nicole’s mother had been a food critic and her father a wine enthusiast and collector, and her husband had long been passionate about wine and winemaking, so the couple decided to accept the challenge of transforming the property into the luxury retreat, La Verrière, a wine education center and working vineyard.

Nicole says that by the time they purchased the property, many of the region’s historic high-altitude vineyards had been abandoned.

“People had moved to the valley, where they could get yields that were much higher than anything in the mountains,” she explains. Vintners sold their grapes to local cooperatives to pocket as much money as they could, and the quality of the region’s wines suffered.

But Nicole wasn’t interested in making a simple table wine that could be purchased next to the shampoo and mayonnaise in the supermarket. Nor did she want to start a “vanity project” by planting vines in prestigious appellations just to assure high scores from influential wine critics. Her goal was “to make really thrilling wines that are qualitatively interesting but also stylistically original.”

As luck would have it, the site of their vines, 2,000 feet up the mountain, is especially propitious. The wines produced at that altitude have a striking minerality that is lacking in wines produced from grapes grown at lower elevations.

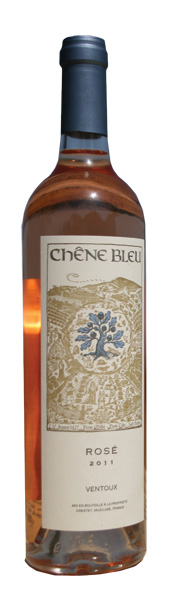

Along with four bottlings intended for earlier drinking, two longer-aged vintages of Grenache- and Syrah-based reds have now been released under the label Chêne Bleu. As wine connoisseurs have noted, the younger wines have pitch-perfect structure, while the longer-aged cuvées are remarkably complex and self-assured.

Having met with critical success in Europe and Asia, the Rolets are ready for the next challenge: introducing their wines to America. They have already found a top-notch importer, and by year’s end, Chêne Bleu should be available in a number of wine stores and restaurants across the United States. But Nicole prefers a more personal approach to marketing, like the small tasting she recently held for the press at the upscale Bar Boulud in Manhattan. It’s her way of showing the world that Chêne Bleu wines are indeed “exceptional and unique.”