Activist Art

From a team of lawyers battling gender discrimination in the American workplace, to a documentary filmmaker focusing his lens on global climate change and its impact on the people of east Africa, Vassar’s alumnae and alumni have been on the front lines of timely topics, raising awareness, inspiring change, and making the world a better place—environmentally, socially, economically.

That commitment also extends to artists, who use their art as a form of subtle or not-so-subtle activism. It is the opposite of “l’art pour l’art”—art for art’s sake, divorced from moral, utilitarian, or edifying function. Rather, it is art meant to inspire the viewer to action. As Tom Block ’87 noted in a 2008 issue of the International Journal of the Arts in Society, activist art must be “against ignorance, war and abuse,” and must “stand for the greatest human ideals—truth, justice, peace.” Such themes strike at the core of the work of Block and other Vassar artists, who have used their cultivated talents to make the world a better place.

Lewis Rubenstein, Faculty [1939; 1946-1974]

Rubenstein taught at Vassar for nearly three decades, but it was his fresco murals of the 1930s that set him apart as an activist artist. He painted in the Social Realism style, which depicted social injustices, economic hardship, and life’s struggles.

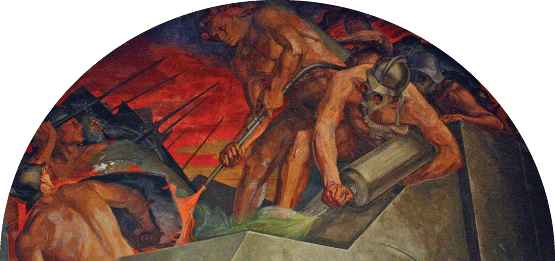

When Harvard commissioned Rubenstein to paint two murals depicting Norse mythology in Harvard’s Germanic Museum (today the Busch-Reisinger Museum), he used it as an opportunity to offer a harsh criticism of fascism, war, and the rise of Hitler in Nazi Germany.

One mural features Alberich, king of the dwarfs, lashing lesser dwarfs. His military-style outfit—including brown boots and breeches—not to mention an unmistakable mustache, makes him look suspiciously like Germany’s rising führer. The other depicts Ragnarök, an epic battle scene. Rubenstein’s interpretation features gas masks, flamethrowers, and canisters of poison gas releasing a green plume, as chlorine did during World War I.

According to arts scholar Bernice Lippitt Thomas ’49, who studied under Rubenstein during her time at Vassar, the murals raised the ire of the German Consulate General in Boston, and although Rubenstein demurred, claiming the murals were

merely modern stylings of old legends, Harvard hid them behind panels to quiet the criticism. Decades later, though, Rubenstein admitted to the deeper meaning behind the work, and Harvard removed the panels, partly due to an appeal from his wife, Erica Beckh Rubenstein ’37, making Rubenstein’s art viewable to a new generation.

Through August 13, the BCA Center in Burlington, Vermont, is hosting a Rubenstein exhibition.

Tom Block ’87

Block describes the continuous thread that weaves its way through his diverse art projects as the exploration of “the spiritual life of humanity and our sometimes-sad shared reality.” No project may embody that nexus more than his ongoing Human Rights Painting Project. Started in 2002 and undertaken in partnership with Amnesty International, it highlights the struggle for human rights around the world—the oppression of women in modern-day Afghanistan, abuses of the criminal justice system in India, China’s annexation of Tibet and suppression of Tibetan Buddhism, the plight of refugees in Kosovo, and the implementation of the death penalty in Texas.

Visit Block's website.

Mary Daniel Hobson ’91

“Troubled by the increasingly fearful and dark tenor of the world, I began this series dedicated to hope,” notes Hobson of her project, Milagros, translated Miracles. Hobson asked people to write down a wish for positive change in the world on their arms, photographed them, then created collages out of the words and images. Responses included “kindness,” “peace,” “love,” “the first woman president,” “no littering,” “focus on the positive,” “conserve ecology,” and “children’s happiness.” She modeled her Milagros artworks after Mexican milagros, small talismans—often shaped as hands, legs, hearts, or babies—hung in churches and containing a person’s wish for a miracle. “Arms and hands are the focus of my series,” Hobson noted, “because it is with our arms and hands that we build tangible results in the world.”

Visit Hobson's website.