Alberto Goes to the Prom

It was the night of the prom, Signorina Agnes’ boyfriend was sick. Would Moravia be her escort? He agreed. Taking him possessively by the arm, Agnes brought him to her room and explained the rituals surrounding the dance card and its sixteen dances.

In October 1935 the handsome 28-year-old Italian novelist Alberto Moravia arrived in New York at the Casa Italiana at Columbia University. His first novel, Time of Indifference, had been a huge success. His second novel, Mistaken Ambitions, had not.

(Government censors had instructed journalists to ignore it.) Earlier that month Mussolini’s army had begun war in Ethiopia. In November the League of Nations imposed sanctions on Italy. It seemed like a good time to leave Rome. A few years before, armed with introductions from art critic Bernard Berenson, Moravia had spent time in London and Paris meeting intellectuals, sending back an occasional travel piece to Italian newspapers, and entering into brief love affairs. He was ready for New York.

But he did not fall in love with New York. The lasting effects of the stock market crash left him with little faith in capitalism. He saw men selling apples on the streets. He drank a lot, played strip poker, and frequented prostitutes. He complained about “the frightening squalor” of his room on Amsterdam Avenue. He again wrote travel articles and sent them to the pro-government Gazzetta del Popolo in Turin. These first-person accounts read like short stories. His excursions included a service by Father Divine on Lenox Avenue in Harlem, a burlesque show, and the toy department at Macy’s. Perhaps he planned to collect these accounts into a book about America, much as his predecessor at Columbia, Mario Soldati, had done that very year. In any case, these vivid sketches were not reprinted until 1994, when they appeared posthumously in his collected travel writings.

As a distinguished visiting intellectual from Italy, Moravia delivered a lecture on the Italian novel at Columbia, which he repeated at Smith and then at Vassar, coming to campus on Saturday, February 22, 1936. His account of that visit appeared later that year in the Gazzetta del Popolo and, until now, has never been translated into English. What follows is based on that account.

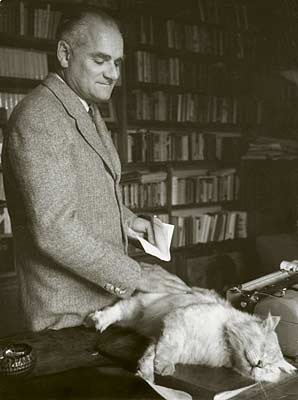

Alberto Moravia in his study with his cat, Famossimo,

named for the Italian author

It had been a hard, snowy winter. (According to The New York Times, 23,000 shovelers could not keep up with the glacial crust that covered Manhattan streets. Drift ice fringed the Battery. The Staten Island ferry navigated by compass alone. Above Riverdale, people fished through holes in the frozen river.) As the train sped up the Hudson on that bright clear Saturday morning, Moravia repeated to himself the names of the five novelists he was to discuss and meditated on “that singular phenomenon which is the transplanting of European culture to America where it becomes a kind of eclectic anatomy of desiccated, lifeless bodies.” European intellectuals then, as now, charged that America was better at conserving culture than creating it; it was a museum culture. The premise that Europe had a culture, which Americans needed to study, did not seem to apply in reverse. One wonders what Moravia knew of American culture before arriving in New York. Had he read The Federalists Papers, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Mark Twain? Probably not, since they mostly had not been translated into Italian. He may have read Moby Dick in Cesare Pavese’s translation of 1932.

“It was a beautiful, extremely cold day. The sun filled the smoky air of my compartment with intense, radiant light. Over a totally white Hudson there rose a winter sky of that pale, shivering blue color which seemed to retain the bright white dusting of a snowstorm.” Once in Poughkeepsie, he hopped into a cab, which, after a bumpy ride through high snow banks, brought him to “certain red walls like those of a castle.” In front of Main Building, the novelist’s (and amorist’s) practiced eye noted the young women hurrying by “dressed in every possible color, casually wearing leggings but no hats. Many wore short fur coats and even ski pants.” They immediately took him over. “A couple of these youthful smiling lasses welcomed me and led me through many large rooms into an attractive parlor on the ground floor of one of the college’s buildings.” He describes this building, which was probably Josselyn, as a kind of museum: “beautiful antique furniture everywhere, carpets, mirrors, well-made pictures; everywhere the aristocratic, slightly cold style of the Anglo-Saxon eighteenth century, George Washington, and Queen Anne.” Instead of a lecture hall he was surprised to find himself in “a vast comfortable parlor, with groups of armchairs, curtains on the windows, and green wall paper.” Moravia “began observing the girls, all of whom were attractive, to tell the truth, with that fresh, innocent, slightly conventional look common to American women at almost every age.” He took a cup of tea, was surprised to see “about a hundred” young ladies “arrange themselves on the armchairs, the arms of the armchairs, even on the floor, crossing their legs Oriental fashion.” Not too many years later, such decidedly non-European postures would be immortalized in Anne Cleveland’s ’37 and Jean Anderson’s ’33 frescoes in the Alumnae House Pub.

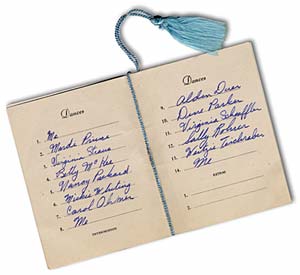

At the last minute, Moravia recalled a recent statement that the Italian novel did not exist, and decided to contradict it in his talk that afternoon. The extemporaneous lecture was a success. He appears to have spoken in Italian. The assembled young ladies followed him attentively. Afterwards, “a large, authoritarian, bespectacled woman” came forward. This was not the department chair, Guido Ferrando, but probably Maria Teresa De Negri , a young woman from Pisa (who later became the department chair under her married name of Piccirilli). The woman “quite ceremoniously introduced” Moravia to Agnes, a “shapely blond” student “of clearly Germanic origin,” who while “fidgeting and blushing” had a favor to ask. (At this point in the account, readers of Moravia’s first novel can not help but be reminded of the awkward and attractive Carla.) It was the night of the prom, and Signorina Agnes’ boyfriend was sick. Would Moravia be her escort? He agreed. Taking him possessively by the arm, Agnes brought him to her room and explained the rituals surrounding the dance card and its sixteen dances. Scrutinizing the furnishings in her room, Moravia deduced she led a comfortable upper-middle-class family life. He found her “singularly intimate even in these slightly distant and awkward relations.” She showed him her blue silk dress and explained how to phone in a last-minute order for a gardenia corsage. (“Corsage” was a new word for him.) Her girlfriends “were in high spirits and giddy at the idea of the dance.” They began to joke among themselves. Suddenly, in a scene that would not be out of place in Time of Indifference, “one of them ran into the hall, the other followed, and the two of them fell down together, sliding on the shiny waxed floor.”

Later, probably in Main Building, Agnes introduced him to “the entire teaching body,” which reviewed all the young couples as they passed by. “Keeping our columns with the solemnity of a wedding ceremony, we entered a dining room full of small candlelit tables agleam with crystal. There were easily two or three hundred of us. The food was poor, there was a lot to drink.” The young ladies moved to a “theater,” undoubtedly Students’ Building. Then came the photographer’s magnesium flash, the signal for the famous New York band to strike up the first dance, a solemn number inaugurating the Grand March with which Moravia was unfamiliar. “Up in the mezzanine the excluded girls leaned down to look with envy.” Following tradition, Moravia never got to dance with Agnes, who carefully introduced him to each of his sixteen partners. The formalism of it all led him to conclude that American life was “at bottom aristocratic.” After the dance, Moravia and Agnes and another couple got into a car and raced through the snow at breakneck speed to what he called a “cabaret”—“a fake wood cabin” on a back road, with deer heads on the wall and food served “automat style.” The tipsy girls “hiked up their voluminous dresses above their knees, like chorus girls dancing in New York.” The other young man was also tipsy. Their car swerved into a snow bank. They had to walk back to the college, reaching its “red walls” around dawn.

By John Ahern

Photo credits: Moravia: John G. Ross; All Others: Special Collections, Vassar College Libraries

Vassar Professor of Italian John Ahern’s complete translation of Moravia’s article, “Collegio femminile americano,” is available in the Online Additions section of this issue.

The Vassar Quarterly welcomes answers to Ahern’s questions and will report back any interesting responses.

Vassar Proms: A Changing Tradition

Hannah Lyman, the first Lady Principal of Vassar, doubted that dancing was in accord with Christian principles, and before she was hired she challenged President Raymond about the propriety of students dancing. In spite of Lyman’s lack of enthusiasm for dancing, a few years after the college opened recreational dancing sometimes occurred in Main Building’s “J Parlor,” one of the parlors leading from the 12-foot wide, second floor central corridor. The wide corridor had been explicitly planned by James Renwick, architect, at the wish of Matthew Vassar, to encourage student winter exercise. During the same period the physical education instructor required all students to participate three times a week in classes, which included aesthetic dancing to music.

The most popular debutante New York orchestras, including those led by Glen Miller and Tommy Dorsey, fitted the Vassar Junior Prom into their schedules.

After these various beginnings, it is no surprise that as the century went on, dancing of all kinds persisted at Vassar in spite of a latent reticence in the early administration. Students of Vassar history can surely guess that the year of strong administrative encouragement of proms would be 1915, when Henry Noble MacCracken became president. MacCracken, 34 years old and immersed in the pre-war changing ideas about student culture, came to the college as president six months in advance of his inauguration in October 1915. During those six months he allowed many changes in student life, encouraging the students who had been desirous of forming a Suffrage Club and a Socialist Club to do so, and accommodating many other pent-up student demands.

The junior prom that year was the chief social event of the college year according to the 1915 Scrapbook. “It was the only dance to which the juniors [were] allowed to invite their male friends.” It included a grand march for the first time, with the president leading the way.

The junior proms of the ’30s and ’40s, held in Students’ Building, kept to a pattern and were received into Vassar legend. The most popular debutante New York orchestras, including those led by Glen Miller and Tommy Dorsey, fitted the Vassar Junior Prom into their schedules. The prom was always held around Washington’s birthday weekend, and expectation for the event was keen throughout the preceding fall. The sister class (freshmen) and other members of the college community stretched their heads over the balcony railings above the dancers and took the prom in. Often, as in Moravia’s account, some students would take off for a roadhouse after the prom was over.

Through Moravia’s eyes, we see how the event looked to an Italian visitor who unexpectedly attended a Vassar Junior Prom.

Elizabeth Adams Daniels ’41, Vassar historian

The VQ invites readers to share memories of their junior proms.

Photo credit: Special Collections, Vassar College Libaries