To Have and To Hold: The Same-Sex Marriage Debate

On February 14, 2004, Deirdre Bourdet ’00 and Leslie Caccamese ’00 attended a rally in Sacramento, California, in support of Assembly Bill 1967, the proposition that would legalize same-sex marriage in that state.

While the couple intended only to show their support for the bill and for the several same-sex couples in attendance who had been married just the day before by San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom and City Assessor Mabel Teng, the plans for the day quickly changed. Seeing the “tearful embraces and tender kisses” of couples who, Caccamese remarked, “had been together for decades and staunchly fought for the right to marry for an equally interminable period” left her and Bourdet certain of their desire to be married as well. “However questionable the marriage’s legal future might have appeared to us at the time . . . we felt we had to go for it,” Bourdet said. So the couple raced from Sacramento to San Francisco “to be the very last couple in line to marry on Valentine’s Day!” Unfortunately, after a three-hour wait, Bourdet and Caccamese, along with several hundred other couples, were sent away and told to try again the next day. And that’s precisely what they did: Bourdet and Caccamese were married at the San Francisco City Hall on February 15, 2004 (pictured, Cassamese, left, Bourdet, right).

The couple hadn’t opted to have any type of formal commitment ceremony before their marriage. “We didn’t want some ersatz marriage, some sort of ceremony that we invented to declare our commitment. I suppose we wanted a ‘real’ marriage—if it is fair to call it that,” Caccamese said. Bourdet agreed, saying that “a commitment ceremony [is] a sweet, but second-class substitute for ‘the real thing.’ I think it’s kind of sad to see people staging an imitation wedding which everyone knows isn’t legal or recognized by most of the world. . . . Why go through an expensive game of make-believe when everyone there knows you’re not really getting married?”

Although the two had been engaged since late 2002, they had only registered as domestic partners with the state of California earlier in February 2004. Still, both were conscious of the limitations of that arrangement. Securing domestic partnership “involves just going to a notary and signing a piece of paper—very unromantic,” Bourdet said. “We only did it for the legal rights [it] provides in our state.” And while the couple does believe that the tax, property, and medical treatment-related benefits of domestic partnership are helpful, their dissatisfaction with partnership alone results from the social stigmatization that couples who are “only” domestic partners, rather than married spouses, receive. Caccamese said, “I think we were more interested in the respect conferred on married people, a communal validation of our relationship.

“The morning after we got married, my parents sent us a message on the emotional obligations and innumerable rewards of marriage,” Caccamese continued. “Our relationship and commitment felt acknowledged and respected more than it had before. We finally felt like our relationship was on equal terms with all the other married couples we know.” Even if their marriage was short-lived—nullified when, in August 2004, the California Supreme Court ruled that Mayor Newsom exceeded his authority in issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples—Bourdet feels, “People really did treat us differently for the six months we were married, whether they knew we had married someone of the same sex or not. It’s as if our marital status suddenly made us worthier of respect, and that we were suddenly part of a different club with a new social power.”

The struggle for and against same-sex marriage has been played out on a much larger scale, extending far past Bourdet’s and Caccamese’s individual story or the city of San Francisco alone. Several decisions over the last few years have directly impacted the future of same-sex marriage, such as the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act and the March 2004 officiating of same-sex marriages in New Paltz, New York, by village Mayor Jason West. Drawing both national and international attention, these developments have often served only to strengthen the divide between those in support of same-sex marriage and those against. Many experts in both professional and academic fields, however, have discussed the complications of focusing too narrowly on same-sex marriage. In the struggle for securing equal rights that preoccupies those in favor of same-sex marriage, and for safeguarding the sanctity of the heterosexual family unit that preoccupies their opponents, the argument’s common denominator—the institution of marriage—is often ignored.

Vassar Professor of Political Science Mary (Molly) Lyndon Shanley has worked to reframe the same-sex marriage debate in broader terms. For her, thinking about same-sex marriage necessarily involves thinking about and critiquing the pre-existing institution some same-sex couples wish to enter. In a talk titled “Should We Abolish Marriage?” at the Vassar Library in April 2004, Shanley laid out the evolution of her own thinking and research about marriage, outlining how she went from, in late 2002, drafting an essay titled “Spouses and Citizens: A Defense of Marriage as a Civil Status” to, in February 2004, considering the possibility of replacing marriage as a civil status with civil unions for all—regardless of the sexual orientations of those attempting to marry.

Most of Shanley’s concerns in her earlier essay centered on what would become the alternative to marriage if it was abolished. “If you are going to say, ‘Civil marriage is an oppressive and unjust institution, let’s get it off the law books,’ then you have to say what you are going to put in its place.” So-called contractualism—the belief that individually defined contracts could exist in lieu of marriage—has been offered up by critics of marriage as one alternative. While Shanley acknowledged some of the benefits of the contract model—including the freedom from scripture or tradition, the assumed equality between the parties in the initial bargaining position, and the freedom of same-sex couples to enter into contracts—ultimately she found the contractualist position inadequate. “The individualism and emphasis on rational bargaining that are at the heart of contracts rest on misleading models of the person and marriage relationship. Marriage partners are not only autonomous decision makers; they are fundamentally social beings who will inevitably experience need, change, and dependency in the course of their lives. A contract does not express the notion of unconditional commitment, either to the other person or to the relationship.” Moreover, Shanley said, “The understanding of marriage as a contract does not by itself generate the reforms necessary to alter family and workplace structure, welfare, and social services in ways necessary to give both men and women” the opportunity to share equally both public and private work.

Between the publication of Shanley’s original essay and her later one, several national and international developments initiated a rethinking of marriage on Shanley’s part, among them the November 18, 2003, 4-3 decision from the Massachusetts Supreme Court on Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that the denial of marriage licenses to same-sex couples violates the equal protection guarantees of the Massachusetts Constitution. “When the issue [of marriage] is framed as a civil rights issue involving the protection of individual liberty . . . it is natural for me to support the [court’s] majority decision,” said Shanley.

But Shanley realized that in legalizing same-sex marriage the Massachusetts Supreme Court only admitted an additional category of people to the existing institution and did not question what Shanley calls “the less-than-admirable, indeed the oppressive and unjust, aspects of marriage law”: the perpetuation of gender inequality, the marginalization and stigmatization of diverse family forms, and the privatization of support and caregiving concerns that should be the responsibility of society as a whole. “For all its seeming radicalness, the decision of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts reaffirmed a very traditional understanding of marriage, and it assumed that we all know and agree upon what I think are some of the most difficult questions that confront those thinking about justice within families, and justice concerning families’ relationship to the state.”

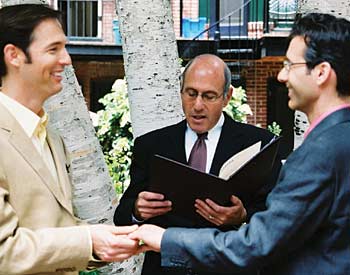

Jon Andersen ’84 (pictured above, left) and his partner Matt Miller (right) shared Bourdet’s and Caccamese’s frustration with commitment ceremonies. Neither had the desire to have a mere commitment ceremony and instead saw marriage as the state to aim for. Said Andersen: “Marriage is universal, readily understood by everyone in our culture. Isn’t that the point?” Miller agreed: “I think commitment ceremonies are great, but a wedding is seen as more conventional and legitimate.” After living together for over eight years in Boston, the couple took advantage of the legalization of same-sex marriage in Massachusetts, applying for a marriage license on the first day they could—May 17, 2004—and marrying on May 20 at the Arlington Street Church, a Unitarian church in Boston. “It was a very empowering experience, and I don’t think I would have felt quite the same after a commitment ceremony—it feels second-class when you don’t have the choice. For straight people who do [have a choice, a commitment ceremony] is an ‘alternative’ choice, and they can feel cool about” choosing that option, Miller said.

The language of validation and empowerment Andersen and Miller use in describing their marriage mirrors that used by Bourdet and Caccamese when talking about their union. And despite the kinds of injustices critics like Shanley or Citron think characterize marriage, both couples still insist that being offered the equal choice to be married, as heterosexuals are, is the important issue. Bourdet and Caccamese jointly said: “Marriage is not more just or unjust than any other body and system with which we daily engage. Just as some heterosexual couples decide to refrain from marriage because they believe the institution antiquated and unjust, so should each individual same-sex couple have the right to decide whether or not marriage is for them.” Moreover, Bourdet and Caccamese believe it could be overly pessimistic to decide that same-sex marriage will necessarily carry on some of what Shanley calls the “less-than-admirable” aspects of heterosexual marriage. Caccamese said: “Same-sex marriage offers a somewhat bankrupt institution an opportunity to adapt to social structures that have been dramatically altered. Opponents of same-sex marriage are keen on the argument that [it] would ‘change’ marriage. While proponents of same-sex marriage claim that this is not the case, we do believe that same-sex marriage will change the institution of marriage and it will do so for the better.” In fact, according to Bourdet and Caccamese, same-sex marriage can perhaps provide a more equitable model for the whole of society: “As a same-sex couple we have more leverage to decide the roles we will assume in our relationship based on our individual interests and strengths, [therefore] those roles are dynamic. If same-sex marriage means the country must confront couples who choose their roles based on understanding and consensus, well then it is no wonder people object to same-sex marriage—they’d have to confront and, horror of horrors, challenge the status quo!”

Challenging the status quo for anyone hoping to be married is a goal, for critics like Shanley, in reformulating the way we think about marriage, not denying same-sex couples rights equal to heterosexuals. Civil marriage must be abolished, Shanley argues, in order to separate finally the overlap between church and state that characterizes marriage as it exists now. Shanley said, “On the day after the Goodridge decision was handed down, President Bush said he would work to see that the institutions of government supported ‘the sacred institution of marriage.’ I read that and thought, it is not the business of government to be supporting ‘sacred institutions.’ Civil marriage is not a sacred institution. And indeed, our practice in the U.S. of authorizing religious ministers to act as officials of the state in registering marriages promotes that confusion.” The remedy that Shanley foresees is the replacement of marriage with the universal implementation of civil union, “not civil union as an alternative to marriage for same-sex couples, let me hasten to say, but civil unions as the form of committed adult relationship recognized by the state for everyone, gay or straight or transgendered or bisexual.” The term marriage would be retained, but could—and should—be used only “as the term for a social or sacred institution,” she said. “After uniting ourselves in the eyes of the state, those of us who think marriage is sacred or sacramental, strengthened by the recognition of a vibrant social group or community, should solemnize our unions in the presence of that congregation or community.”

Still, Andersen believes that preserving marriage in such a capacity—because some churches would continue to refuse the solemnization of marriage for same-sex couples—is problematic. “Wherever marriage exists for heterosexuals, civil unions for homosexuals will have second-class status and be tailored to the whims of legislators.”

And marriage has come to be so strongly associated with the “official” confirmation of one’s love for another, Andersen argues, that preventing same-sex couples from being married, even if they do have the legal right to a civil union, would further complicate the understanding of same-sex commitment. Andersen said: “Though [Matt and I had] thought of ourselves as being in a committed relationship akin to marriage, we discovered that our families and heterosexual friends were less clear about our commitment intentions until the marriage ceremony was applied to it. In our greater culture, that’s how family is defined. It’s understood and respected; if you’re riding in an ambulance, or picking out a coffin, or dropping your kid off at school, or getting a ‘family’ rate at Disneyland, you want others to have immediate understanding that you are a family unit, with its rights, privileges, and responsibilities. Marriage provides that—and a way to tell the world we love each other.”

Same-sex marriage will no doubt continue to be debated across the world—in courtrooms, in classrooms, in living rooms. But so long as marriage in general remains a topic of debate, so will same-sex marriage. Only by questioning and knowing exactly what type of institution same-sex couples might be assimilated into can we really come to understand more fully just what it means for same-sex couples to be married.

If you would like to read more about the history of marriage and alternative family structures, check out this list of sources by Shanley and Citron.

Shanley, Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England, 1850-1895 (Princeton UP, 1989)

Shanley, Making Babies, Making Families: What Matters in an Age of Reproductive Technologies, Surrogacy, Adoption, and Same-sex and Unwed Parents’ Rights (Beacon, 2001)

Shanley, “Just Marriage: On the Public Importance of Private Unions,” in Just Marriage, ed. by Joshua Cohen and Deborah Chasman, (Oxford UP, 2004)

Citron, “Will it be Marriage or Civil Union,” in The Gay & Lesbian Review, 11(2), 2004

Citron, “Lawrence v. Texas: A Victory for Liberty,” in The Gay & Lesbian Review, 10(6), 2003

Professor of Political Science Molly Shanley and lawyer and academic Jo Ann Citron ’71 led an online chat discussion of same-sex marriage on Tuesday, January 25, 2005, at 8:00 p.m. EST. A transcript of the lively discussion can be found in the Online Additions of this issue.

Save the Date!

The Lesbian and Gay Alumnae/i of Vassar College (LAGAVC) will hold its annual spring conference on campus April 29 – May 1, 2004. For more information, contact AAVC at 845.437.5453.