Award-winning Actress Frances Sternhagen '51: From the Outside In

Frances Sternhagen ’51 may not be a household name, but she is a household face —one of those strangers welcomed weekly into living rooms across the nation. She is familiar to millions of television viewers as Carter’s grandmother on ER, Cliff’s mother on Cheers, Virginia in Misery. But beyond such celebrity stints, Sternhagen has a solid reputation for acting excellence, particularly in theater; she has won two Tonys (for The Good Doctor and The Heiress), two Obies and two Drama Desks, and has been inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame. In November, the accomplished actress and mother of six returned to campus as President’s Distinguished Visitor—the highest recognition Vassar College bestows on its alumnae/i (it comes complete with a medal). She visited classes, had an hourlong Q-and-A exchange with drama students, and gave a public lecture and reading.

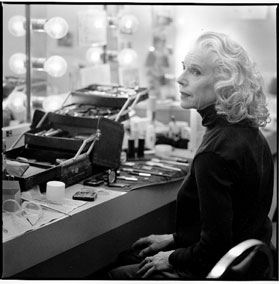

Offscreen and offstage, Sternhagen does not look or play the part of glamorous or exotic actress. With her small frame and hair curling down past her shoulders, she exudes the aura of a young girl, so when she talks about being a student at Vassar, it’s an easy leap for the mind to make.

At an interview on campus she wears knee-high brown boots and a colorful scarf that somehow suggest a suburban mom and a worldly performer all at once. Her voice is so delicate, it is difficult to remember how successfully it can fill a Broadway theater. That is, until she puts it to work in the Villard Room and conjures up an influential Vassar drama professor in the act of directing students from the back of Avery: "I don’t believe you!" shrills the infamous and "strangely neurotic" Mary Virginia Heinlein. "I’m going home. I don’t believe you!"

Heinlein may not have been gentle, but, says Sternhagen, who nevertheless had great respect for her teacher, "she had an amazing ear for the truth." The professor’s influence has extended over the length of the actress’s career. Ever since her college lessons Sternhagen has sought the truths with which she could deliver believable characters. "The search for the truth of a situation is where your energy should be addressed," she says.

It is, perhaps, a little surprising in this age of explaining everyone from the inside out to hear Sternhagen declare herself to be an actor who works primarily "from the outside in." She explains, "I like to be the Minister of Silly Walks. I like finding how a character speaks and walks and dresses." Like a musician who finds the spirit of a composition by replaying phrases, Sternhagen finds the souls of her characters by repeating her lines again and again. "I find that I have to say the lines over and over to myself until I can hear the truth in them." Her talent in this area is clear not only to audience members but to her castmates as well. Jon Tenney ’84, who played Morris Townsend to her Aunt Penniman in The Heiress on Broadway, testifies to the truthfulness Sternhagen brings to a role. "It was very easy to feel grounded in working with her, because she was so real and in the moment. Couple that with the ability to do period work, and her voice and her physical training—she’s terrific. But the core of it was an incredible naturalism."

Perhaps surprisingly, Sternhagen waits until rehearsals begin before she starts working on her roles. "Some people learn the part before they even start," she says. "I like to get movement and associate it with what I’m saying and what I’m going to get from the other actors." She tells this to a group of drama majors, who sit on the floor of the Powerhouse Theater and listen to her stories and advice.

She talks to the students of how she arrived in New York in the early ’50s and studied at the Group Theater with Sanford Meisner. It was there she learned the Method, a catchall label that refers to most contemporary American acting. Through the use of improvisation, Sternhagen learned to channel her own emotions into a role, to "live truthfullu under imaginary circumstances" (Sanford Meisner on Acting). Before that, she says, "I was acting, pretending, but it was only working with Meisner that I understood [how] to investigate my own emotions in working on the script."

When one student asks about her favorite role, she answers, "Usually the last one," but she cites Marjorie in The Country Wife as one she especially enjoyed. "I was pregnant with my second," she recalls, "and I bounced around on the floor on my stomach. But my daughter seems to have survived." A Perfect Ganesh, Equus, and The Good Doctor are other favorite plays.

What may be more enviable than the numerous roles she’s played is Sternhagen’s ability to make the leap from stage to screens both big and small. She recalls her first film audition, in 1955, for Burt Lancaster: "In the middle of my audition, he said, ‘Frances, stop acting.’ It was humiliating!" But the experience taught her the difference between acting on film and on stage. "You don’t use your face as much in film—you’ve got to keep it contained. It mostly has to come through your eyes. In the theater . . . you have to throw it out to the back of the house."

Though she didn’t get the part in Lancaster’s film, Sternhagen went on to appear in others, Independence Day, Outland, and Doc Hollywood among them. Sternhagen does say no to projects, the names of which most people wouldn’t recognize because they never amounted to much—a tribute to her taste and foresight. However, she’s no snob—she has happily performed for her bread and butter (and her children’s college tuition) in television commercials. In one ad for Gillette razors she played mother to Henry Winkler, then on his first job. To actors who hold their nose at the thought of advertising work, she has some practical advice: "Think of it as children’s theater!"

But her stongest advice to this room full of young would-be actors is to work in live theater. It gives the best training, she says. "Often in film . . . you shoot the last scene on the first day. [In theater] you spend more time learning the process, and you have the opportunity to go through a story from beginning to middle to end." Unfortunately, she points out, it’s difficult for an actor to develop a career that spans all media, and she holds geography responsible for this. "When the movie business started and moved to California because of the weather" she says, "it meant we had 3,000 miles between theater and the other culture, which is film and television." Consequently, she says, many young actors become famous doing film and TV without the benefit of the discipline one develops in theater. She envies the British their small country, where it’s easier to jump back and forth between stage and screen.

Sternhagen is enthusiastic about what’s on television today and has enjoyed her work on shows such as ER and Cheers, but she laments the homogenization television promotes. When the daughter of a friend was cast as Emily in a TV production of Our Town, she asked Sternhagen for coaching on the New England accent, only to report later that they’d decided to nix the accent for a more universal appeal. Sternhagen was outraged. "Thornton Wilder made that play in a specific place, in a specific time," she says. "The universal is perceived through the specifics; it’s bound through all the little things. There’s no such thing as ‘truth’ in capital letters, it applies to every moment."

One student wants to know if it was difficult for a couple in show business (her late husband Tom Carlin was an actor as well) to raise six children. She grants that it wasn’t easy, but "it’s harder now," she says thoughtfully, "because in those days, you could whack a child." She executes this line with such perfect timing that it takes the group a moment to erupt in laughter. Whacking aside, Sternhagen seems to have passed on her passion for theater to her half dozen offspring—all of them are in the arts in some way, though they support themselves through other means. Her brood includes an actress, a rock musician, and a teacher of performing arts. A grandmother of six as well, Sternhagen confides, "I’m not a very good grandmother. I’m too busy."

"Busy" is an understatement. In January, Sternhagen was scheduled to appear at the Florida Stage Company for a repeat performance of The Exact Center of the Universe, which appeared Off Broadway in 1999. After that, who knows? Long and impressive though her resume may be, Sternhagen’s is still the life of an actor, and the plot unfolds slowly and unpredictably. "It’s been a rewarding life," she says. "It’s through working on characters in plays that I’ve learned about myself, about how people operate." But perhaps the most critical lesson in that regard came from another Vassar faculty member: Professor of History Evalyn Clark. Sternhagen started out as a history major at Vassar, and one day, she recalls, Clark asked why she wasn’t majoring in drama. Sternhagen never forgot the conversation that ensued. "When I said I don’t think you should major in something that is just fun, she said, ‘For me, history is just fun.’ It was a lesson that you should always try and do what you love, whatever that is, and if you’re able to make a living at what you love to do, you’re terribly lucky."

That, perhaps, is the biggest truth of all.

Writer Bronwen Pardes has worked in regional and downtown New York City theaters.