Forbidden Fruit: Sexuality Education

Sex happens. Sexuality education often doesn’t. And when it does, it is almost always controversial.

"I used to think race was the issue that divided Americans," says Susan Neuberger Wilson ’51 , head of the New Jersey Network for Family Life Education and one of four Vassar leaders in the family planning field featured in this issue. "But now I think it’s sexuality." Who in their right mind would enter such an arena? In fact, many of the best minds have become passionate about it, including the Vassar grads profiled here. The occasion for our cluster of stories is publication of a book this past summer, Teaching Sex: Shaping Adolescence in the 20th Century by Jeffrey Moran, in which one Vassar graduate,Mary Steichen Calerone ’25 figures prominently as "the grandmother of sex education." Moran’s essay on Calderone is adapted from that book. Our other three stories feature alums presently at work in the field and front lines of the family planning movement, a movement that has attracted the support of a great number of Vassar alumnae/i. Individually and together, these four graduates embody intelligence, commitment, passion, humor, and a willingness to endure the slings and arrows of contentious dispute. Some call that combination Classic Vassar.

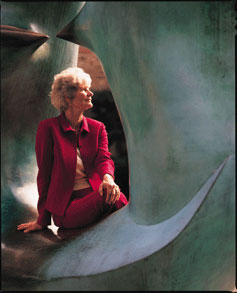

Susan Newberger Wilson ’51 Brings the Sex Ed Message Directly to Teens

"That was the message in the ’40s" Wilson says. "No premarital sex." Though she doesn’t remember the details of that talk, Wilson today refers to Calderone as a heroine. and as executive coordinator of the network for family life education, Wilson is treading a path very similar to the one Calderone pioneered some three decades ago when she founded the Sex (later Sexuality) Information and Education Council of the United States.

Nevertheless, the message in Wilson’s brand of sexuality education goes way beyond "waiting for Mr. Right." The Network for Family Life Education, based at Rutgers University’s School of Social Work, is a resource center that supports sexuality education for adolescents by providing technical assistance to school boards, community health centers, and government offices. Sex Etc., the Network’s newsletter, is Wilson’s proudest accomplishment. Written by and for teens, 580,000 free copies are distributed each year to 3,000 schools and community organizations, and its online version gets roughly 3,000 hits a day. Articles cover everything from masturbation to abortion laws to condom use. The Website’s "ask an expert" section is staffed by adults who answer questions candidly, using jargon kids can relate to. Frequently Asked Question’s include "What is oral sex?" and "How do you French kiss?"

Amidst protest from conservative organizations like Focus on the Family, which claims Sex Etc. encourages kids to have sex, the newsletter received an award in 1997 from the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. There are schools that refuse to use it–especially when it features an article about abortion–but Wilson also hears from teachers who virtually plan their curricula around the newsletter because they find that their students respond to the peer-to-peer nature of it.

Nevertheless, Wilson says she has learned lessons from those whose views contradict her own: "There is a way of presenting information that does sometimes make [students] feel that they’re ‘the last virgin,’" she acknowledges. "That’s why there has to be a balance in what you teach. And I have learned from the opponents of what we call comprehensive sex education that there needs to be as much respect for people who choose abstinence through school or college or until marriage as there is for those who decide at 17 and in a loving relationship to have intercourse. I think that’s what good sex education does. It makes sure that all viewpoints are discussed and equally respected and honored."

Like Calderone, Wilson was a drama major at Vassar, and she calls upon her acting training when she finds herself testifying before the Senate on behalf of sexuality education. More important, she says, "Vassar taught me how to get the facts, form my own opinion, and make my own decision. And I think that’s what sexuality education ought to be–good pedagogy."

After getting a master’s degree in education, Wilson started her career as the education reporter for Life magazine. She went on to teach reading in inner-city schools, and in 1978 was appointed to New Jersey’s state board of education. When the commissioner of health came to a meeting and expressed concern over rising rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, "I asked her at what age she thought young people needed to know about how their bodies work," says Wilson. "At that point I thought that was all they needed to know." That question changed her life, she says. The president of the board subsequently formed a subcommittee to focus on sexuality education and asked Wilson to lead it. When her term on the board expired in 1982, she was asked to go to Rutgers to run the Network, then in its infancy.

Since then, wilson has spent 20 years as an educator and tireless activist for comprehensive sexuality education. in 1993, she organized a coalition of over 30 new jersey organizations to lobby against state legislation that would have required abstinence-only education in public schools. Not only were they successful, but the experience showed Wilson who her allies were. "I used to think race was the issue that divided Americans," she says, "but now I think it’s sexuality. We’re sexual people from birth to death, and yet there’s so much fear and shame. It touches people’s darkest centers."

She continues: "I think when you’re a pioneer, like [Calderone] was, it’s very lonely, and you must have self doubts. I’ve had them to some degree, in bad moments. The tax on her was so relentless. It was very hard and lonely; there weren’t many people out there to support her. That’s different for me. I have lots of allies, which is very comforting because your allies are the ones who have to get out there and do all the hard work. I don’t think she had that luxury."

Now looking toward retirement,Wilson confesses to "grave concerns" about the constraints on sexuality education in schools. She feels passionately that good sexuality education takes its cues from its students, and the message she gets from them is "too little, too late." She insists that in a culture as sex-saturated as ours, education should start as early as kindergarten, and that it shouldn’t be didactic. "Mary [Calderone] heard a lecture and gave a lecture," says Wilson, "but a lecture shouldn’t be part of sexuality education." Instead, Wilson advocates small-group conversations between young people and adults based in large part on the questions and concerns of the students; groups should be both single- and mixed-gender. "You can’t talk about sex in the back seat of a car if you can’t talk about it in a classroom," she says.

In the face of AIDS, Wilson thinks educators have allowed their fears of the consequences of sex, rather than the needs of kids, to dominate sexuality education curricula. "We think we’re going to persuade kids better by pointing out that sex equals disease, danger, and death. I don’t think we ever stress the positive aspects of human sexuality."

Wilson sees the government as the biggest impediment to the kind of education she envisions. The 1996 Welfare Reform Act earmarked $250 million over five years for abstinence-only education. Aside from disagreeing fundamentally with this approach, Wilson points out that there has been no research done to prove its effectiveness. Still, she finds solace in the overwhelming response to the Network’s Website, and she feels certain that if circumstances don’t change in public schools, more and more kids will be turning to the Internet–many of them to Sex Etc.–for information.

For someone who stumbled into her career by sheer accident, Wilson has approached her work as an educator and advocate with astounding passion. In retrospect, she is glad to have "touched the hem of Mary Calderone’s garment," and is proud to consider herself "one of her heirs."

"I feel a sense of gratitude at being given this work to do," she says. "It’s given me joy, it’s given me frustration, it’s given me anger. But when I hear from a kid that our site is a blessing–what more do you need?

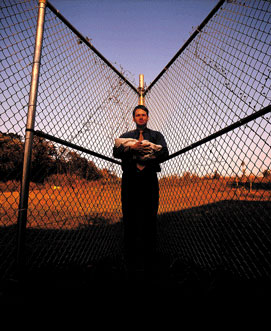

David Nova ’83 Is Taking a Planned Parenthood Clinic in New Directions

Hired as director of public affairs for planned parenthood of the blue ridge in 1989, Nova was promoted to chief executive officer in 1997. since then, he has worked not only to defend freedom of choice, but also to broaden perceptions of the term. In 1999 his affiliate became the only one in the nation to provide, in conjunction with the Children’s Home Society, onsite adoption services. And last May they began offering prenatal care services, which, according to Nova, makes them the only medical facility in the country to provide all three pregnancy options–motherhood, adoption, and abortion–under one roof. "Every pregnant woman who comes into our clinic," he says, "comes with unique circumstances. I have tried to create a medical and educational environment that is flexible enough to meet the individual needs of each of our patients."

Providing options for pregnant women makes up only a small part of the affiliate’s efforts. The majority of the group’s work is geared toward sexuality education and the prevention of unwanted pregnancy. Eight staff members offer sexuality education for children in nursery school, postmenopausal women, and everyone in between. Parents of young children and nursery school teachers, for example, are taught how to instill children with a sense of privacy, respect, and boundaries. At the fourth-grade level, Planned Parenthood of the Blue Ridge provides an education program–Educating Children for Parenting–in which a parent and newborn visit the classroom every few weeks. At the same time the pair is the focus for lessons that teach traditional school subjects–"How much more does the baby weigh?" might be the basis of a math lesson, for example–parent and child also model parenting and nurturing skills. "It plays on the natural curiosity children have about infants," says Nova.

Another program, called Sex or Not, targets 11- and 12-year-olds, especially those in low-income areas; youngsters are taught about the importance of delaying pregnancy with the hope that they will become well-informed peer educators. Yet another effort focuses on the partners of women who come to the clinic for an abortion. In group sessions, counselors emphasize to the men their important role in supporting the woman after the abortion, and of course, contraception. The counselor, says Nova, "makes sure they recognize they’re at least half responsible for this unintended pregnancy and preventing future unwanted pregnancies."

When Mary Steichen Calderone ’25 began working for Planned Parenthood, it was illegal in most states to distribute contraception to married couples. "The battles we’re fighting today are different," says Nova, who calls Calderone a "giant among a distinguished list of women who transformed reproductive health and sex education in the last century." Today, contraception is widely available, but even insurance companies that provide coverage for all prescription drugs–indeed, even the ones that cover Viagra–often exempt the birth control pill. Nova sees this as a double standard that needs to be eliminated.

"As the availability of contraception becomes more widespread," he adds, "Planned Parenthood no longer has the burden of being the only provider of family planning services, as it once was. That is both a success and a challenge. It gives Planned Parenthood an opportunity to branch out in new directions. I see [that] in terms of offering all pregnancy-related services and reclaiming the original definition of choice, which means access to all choices, regardless of the one the individual woman will make."

Nova also sees an educational message in providing every possible choice for pregnant women. "whereas from a societal standpoint adoption is seen as a positive option," he says, "very few women consider it." There is a stigma attached to adoption, he explains, as well as many misconceptions about modern adoption in America. "In my opinion," he says, "this challenges Planned Parenthood to ensure women are fully informed of all their choices. In some respects, offering onsite adoption legitimates the option as a viable choice, especially in the minds of our patients who trust Planned Parenthood."

This approach has not insulated Nova and his affiliate from the protests that often surround Planned Parenthood clinics. "Our black employees are called racists and killers of the black race. I am called Hitler, Nazi, owner of Auschwitz in America," he says.

But Nova is undaunted: "We have very good security here and we built a new facility. I helped raise the money for a new headquarters. It has the only drive-through pill pickup window of any Planned Parenthood in the country."

Nova credits his Vassar education, both in and beyond the classroom, as having an enormous impact on his perspective on women’s issues, not to mention his ability to inspire Planned Parenthood of the Blue Ridge to hire their first man. "Professors like Jesse Kalin and Anne Constantinople had a very strong influence on me," he recalls. "But more than that it was the women at Vassar, who were smart, strong, and courageous enough to be vulnerable, who taught me the most. I think I carried those lessons with me, and I was able to articulate that mindset in my interview with Planned Parenthood."

Did Vassar prepare him to work in a field dominated by women? "Put it this way," he laughs, "I didn’t ask anyone if they knew how to use an iron."

Dr. Laurie Schwab Zabin ’46 At the Helm of the Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins

Like Calderone, Zabin entered the field of reproductive health after first exploring another career. by the early 1950s she had earned a master’s degree in english fromHarvard and Radcliffe and was working toward her Ph.D. in English at Johns Hopkins when several events steered her onto a different track. The first was the realization that she had no interest in a year-long course on Old Icelandic literature necessary to complete her coursework; the second was the birth of her first child, delivered by Alan Guttmacher. The obstetrician—who in 1968 would create the Center for Family Planning Program Development, a center for policy studies affiliated with Planned Parenthood Federation of America now known as the Alan Guttmacher Institute—did more than usher Zabin through pregnancy; his conversations with her about population and family planning issues focused her interest on the topics. She attended a meeting of her local Planned Parenthood affiliate, and a new life course was launched. Zabin left graduate school and was soon immersed in the field of family planning as a volunteer for Planned Parenthood.

Among her first projects was work on Planned Parenthood’s efforts to change government policies that restricted caseworkers in most states from answering women’s questions about "what kept rich people from having so many babies." At that time, poor women who visited clinics for health care needs weren’t being given information about contraception options, let alone birth control itself; the only public providers of birth control then were the few existing affiliates of Planned Parenthood. (The AMA opposed birth control until 1964.)

Zabin was an energetic and effective advocate, and her responsibilities as a volunteer grew. In 1962 Guttmacher asked her to join the national board of Planned Parenthood, of which he was then president. She headed the committees on expansion and policy, information and education, public affairs, and international affairs. Together, they developed the standards and policies under which the organization would spread across the United States. In the early 1960s, Zabin also became a professional in the field; she helped establish an inner-city family planning clinic in Baltimore, one of the first to be supported with federal funds.

By the 1970s, after decades of service on state, local, and national boards, and staff experience at the local level, Zabin wanted to engage issues of population and reproductive health from a new angle. "I knew by 1974 that I didn’t want a career in administration," she wrote for her class’s 50th reunion book. "I wanted a larger sphere in which to translate population concerns into meaningful social change, and I missed academia." She returned to Johns Hopkins, this time—in 1974—for a Ph.D. in social demography and population dynamics. "I remember being told when I first interviewed for Hopkins [School of Public Health], ‘It’s not that you’re lacking a prerequisite, it’s that you’re lacking every prerequisite,’ " she says in a telephone interview. "You have to love learning a lot, and I think Vassar’s responsible for some of that."

At the time she began at the School of Public Health, her faculty adviser and a partner were conducting the first surveys of adolescent sexual behavior, and Zabin’s own interest in that area blossomed. She used their data for a thesis, and so initiated her ongoing research and work in adolescent sexual behavior and pregnancy. She earned her doctorate in 1979 and was appointed to the Hopkins faculty. In 1981, she established a Social Science Fertility Research Unit in the Hopkins OB/GYN department.

Over the years, Zabin’s research on adolescent sexual behavior has been critical to the development of education programs. She learned, for example, that half of all adolescent pregnancies occurred within the first six months of sexual activity, and that the younger the age of onset of sexual activity, the greater the risk of pregnancy. In spite of the fact that by the mid 1970s family planning clinics were open to adolescents by law, too often, a teen’s first visit was for a pregnancy test. "[The adolescent] years are so interesting for counselors and educators because during that time, physical, cognitive, and emotional development operate on completely separate timetables," she says. "So the ones who start sex early may be physically mature, but they’re not necessarily able to negotiate a health system or manage contraception."

Her research in the early ’80s demonstrated that the most effective model for school-based sexuality education consisted of educators and counselors within the school encouraging students to visit a nearby clinic.

As a by-product of research she did on the effects of abortion, Zabin discovered another interesting fact: More than half the girls who visited Baltimore clinics for a pregnancy test and got a negative result were pregnant within the subsequent 18 months. A national study yielded similar, if slightly less dramatic, statistics. Zabin sees the moment a girl is in a clinic waiting anxiously for test results as the perfect time for a lesson on contraception, but she has not yet found a successful way for clinics to seize this opportunity. "We’re learning that clinics do marvelous things for girls," she says, but making the experience one that will change a girl’s life "takes a level of case management most clinics can’t pull off. It takes a really powerful counselor and plenty of time."

Accolades, prestigious posts, and honors have flowed zabin’s way almost from the start. she has served on the adolescent health committee of the american college of obstetrics/gynecology, the National Institutes of Health Panel on Long-Acting Contraception, and the White House Initiative on Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention, among many other committee and panel appointments. In 1992 she was given the Irwin M. Cushner Award by the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association for research that serves both health providers and policymakers. She considers her experience in service an important asset to her research and makes a point of accepting at least one invitation each year to work with providers, to get a firsthand understanding of what questions need answering. "My dream," she says, "is that the academic institution not be sitting in isolation. I’m trying to translate to the world at large my feeling that as academics we should be serving the policy makers, working with the providers to answer their questions, and acting as catalysts in bringing them together."

Zabin is currently making this dream a reality on an international level. As director of the Bill and Melinda Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health, she works with developing countries around the world, helping them create their own reproductive health programs. "The institute is developed on the principle that the time is over when we should ship programs out of America and Europe," she says. "Our mission is to develop the capacity, both on the individual and the institutional level, for the developing world to handle their own programs. You can’t create anything as appropriate to a culture as what they create for themselves." Zabin sees her work abroad as a continuation of her local efforts in the ’50s, when she fought to make contraception available to all Americans. "There’s a tremendous demand for family planning services the moment they’re available. We’re no different in this country than in the rest of the world."

In trying to explain what inspires her tremendous dedication to her field, Zabin remains characteristically academic. "Intellectually," she says, "the issues we face as demographers and family planners affect the individual, the couple, the family, the community, the nation, and the world." But an anecdote about her early days in the field reveals a more visceral passion for her work. She recalls a young girl who came to Planned Parenthood for contraception. Zabin told the girl she seemed excited at the prospect of obtaining birth control, and the girl replied, "I just got my acceptance to the Job Corps, and nothing is going to stop me."

"What made me passionate," Zabin says, "was seeing the power of family planning in giving women control over their lives, a power which, once exercised in one dimension of life, can then reach into others."

Photos by Tim Redel